Reading the Guardian recently has brought to my attention the similarities between political events that occur in many different countries and in different parts of the world. I am also struck by the way that these events are treated in the countries in which they occur. The explanations for them most often are sought in local factors, commonly in the activities of local political actors whose actions are often blamed for the unfortunate political outcomes observed. When attempts are made to find underlying common causes, reference is normally made to a broad and fuzzy concept such as “globalisation” or the prevalence of neo-liberal ideology. This seems to me inadequate and I would like to take the opportunity to develop some preliminary thoughts on how to view the causes.

I start by listing the recent Guardian articles that have attracted my attention in this respect and highlighting the themes they raise that I wish to comment on. They mostly refer to the situations that have accompanied the rise of far-right and nationalist political movements.

On Monday Feb 11 Mike Carter, in an illuminating article entitled “The country I walked through deserves better than Brexit” , describes a journey he undertook on foot through England to try to understand what motivated those who voted for Brexit. He says:

on my walk I was shocked by the level of poverty, by the sheer number of homeless people in doorways and parks, and by the high streets of boarded-up shops and pubs, full of payday loan outlets and bookies. People in those former industrial towns spoke of their anger and betrayal, of having been forgotten by Westminster politicians, of their communities having been destroyed as the manufacturing that had sustained them either folded or moved to low-wage economies.

Later on, when talking to someone

who voted for Brexit and to whom Carter suggested that Brexit might make the

economy worse:

He paused for a moment, narrowed his eyes. “If the economy goes down the toilet,” he said, “at least those bastards [in London] will finally know what it feels like to be us.”

On Thursday, February 14 there was a Journal article by Ece Temelkuran entitled “Nationalism has hijacked the hope of the people” .

The article discusses the change in the spontaneous public mood throughout the world that has occurred since the series of uprisings in 2011 at the time of the Arab spring demonstrations. It contrasts the positive feelings and hope for the future of the 2011 demonstrations demanding freedom, democracy and dignity, with the ugly mood of recent demonstrations in many parts of the world where nationalism, xenophobia, vindictiveness and nostalgia have been the dominant themes. At one point the article states

Tahrir Square in Cairo, Gezi Park in Istanbul and Puerta del Sol in Madrid: not so long ago these and other places were sites of protest and hope for radical democratic movements that wanted to remake politics and restore people’s dignity. They were either violently suppressed or absorbed into conventional global politics.

Now, once again, millions around the world are protesting. But the mood and the message have changed. This time they are demanding respect for their “truths” and their divisive political choices. The battle for dignity has been replaced by an aggressive assertion of pride – in the nation, or in a particular version of “the people”.

Later on

But when crowds are desperate enough, it is easy for political actors to reduce the need for human dignity to a vindictive clamour for pride. And this is what rightwing populism does.

It is dangerous and unfortunate that so much public anger is being organised and mobilised by rightwing populists and ruthless autocrats such as Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. They point at journalists, scientists and the political establishment and say: they’re the ones who have been messing with people’s dignity.

Temelkuran then puts the blame on neo-liberalism

By now, even the diehard devotees of capitalism know (as we saw at Davos) that neoliberalism’s economic mechanisms are dysfunctional, its main narrative is collapsing, and that a collapsing story cannot produce inspirational heroes. At the same time people around the world feel the pain of their broken dignity and are angry about having been deceived. This is why they are so eager to be energised by remedies that are too simple to be true, to find visible targets for their anger and, most important, to latch on to false hopes. They are good to go; ready to follow new heroes promising them greatness.

Also on February 14 the Long Read was “How a Slovakian neo-Nazi got elected” by Shaun Walker, describing the rise to relative electoral success of a neo-Nazi in Slovakia. The article begins:

In December 2013, Marian Kotleba, a former secondary school teacher who had become Slovakia’s most notorious political extremist, arrived to begin work at his new office – the governor’s mansion in Banská Bystrica, the country’s sixth-largest city. Kotleba venerated Slovakia’s wartime Nazi puppet state, and liked to dress up in the uniforms of its shock troops, who had helped to round up thousands of Jews during the Holocaust. Now, in the biggest electoral shock anyone could remember in the two decades since Slovakia’s independence, the people of Banská Bystrica and the surrounding region had voted for the 37-year-old Kotleba to be their governor…

…In many of the smaller settlements there were simply not enough jobs, and the most talented people got out as soon as they could. There was a vague resentment at being seen as second-class citizens inside the European Union, and a more acute feeling that the Slovak political class was isolated from the masses and only interested in lining its pockets…

…The city of Banská Bystrica itself is something of an intellectual hub, with four theatres and a well-regarded university, but the surrounding region is regarded as a hinterland of dessicated industrial plants and unprofitable agricultural concerns. Most of the small towns, linked by winding and poorly paved roads, were the sort of places whose names caused metropolitan Slovaks to raise their eyebrows in consternation.

Finally on Saturday February 16, Ian Jack reflects on a visit to Boston, Lincolnshire in an article entitled “The trip from London to Lincolnshire showed me the Brexit divide’s depth”

The trip was to accompany a delegation from Lambeth in London, where I live, the area of the country with the highest anti-Brexit vote (78.6%) to the town with the highest pro-Brexit vote (75.6 %), Lincoln. Early in the text he says:

The station at Sleaford had awnings big enough to shelter bank holiday crowds changing trains for the beach at Skegness. The further we went down this branch line to the coast, the more the sense grew that the past had been greater and busier than the present – a misleading impression because Boston’s population has grown by nearly a fifth since the beginning of the century and the fields around it produce more food than they ever did. T

However, later on he clarifies where the population growth has come from and what the economic activity of the present is:

In Boston, … you need to talk about the migrants, mainly from eastern Europe, who work the new system of food production introduced by polytunnels, longer growing seasons, packing plants, just-in-time deliveries and the changing demands of supermarkets. Some Bostonians will remember a time when farmers employed locally born people as seasonal workers and say, “We did it then, and when this lot go we can do it again.” But that misunderstands the nature of modern agriculture and the transformation of farms into the domestic equivalent of the colonial plantation, demanding a constantly available supply of labour prepared to work long, physically taxing shifts in bad weather, and therefore usually recruited via gangmasters and their scouts from poorer and more vulnerable populations elsewhere.

Migration accounts for Boston’s swollen population, its high rents and house prices relative to other parts of Lincolnshire, and, for a time, it led to overcrowded doctors’ surgeries and schools.

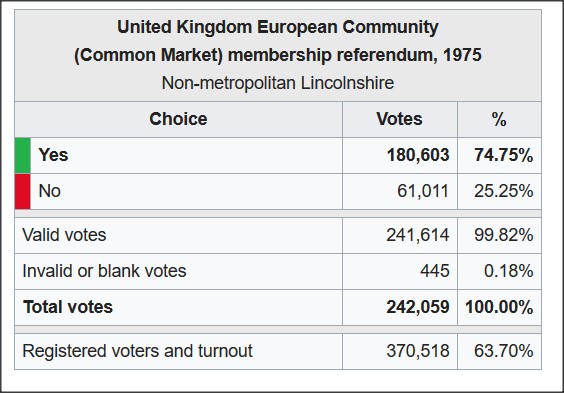

Although East Anglia and the economically similar East Midlands county of Lincolnshire have traditionally been agricultural areas, it is worth noting that it too had its industrial centres and a place in industrial working-class history up to quite recently. The sense that Jack felt that in the region “the past had been greater and busier than the present” refers to a quite recent past. East Anglia had an average economic growth rate in the 1980s and 90s above the national average. I also looked at the results of the 1975 Common Market referendum results. Here they are:

This was one of the highest pro-entry votes in the country.

The speed of recent economic change is highlighted by a paper on the relation between immigration and the Brexit vote (“Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit” by Matthew Goodwin and Caitlin Milazzo, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 2017, Vol. 19(3) 450–464) which states the following:

Boston in Lincolnshire, for example, experienced a particularly high rate of change (of population) in the period prior to the 2016 referendum and subsequently went on to deliver the highest vote for Brexit in the entire country, of slightly more than 75%. Boston was also an area where voters had experienced dramatic demographic change.

In 2015, Boston’s non-British population was 16 times larger than it had been in 2005 (rising from 1000 in 2005 to 16,000 in 2015). Based on our model estimates, had Boston experienced only average rates of demographic change, then support for Brexit would have been nearly 15 points lower.

Explaining the common elements of these stories

I now turn to thinking aloud about the factors that might explain the commonalities in these stories.

The importance of rapid economic changes.

“the high streets of boarded-up shops and pubs, full of payday loan outlets and bookies”

“communities having been destroyed as the manufacturing that had sustained them either folded or moved to low-wage economies”

…

“the surrounding region is regarded as a hinterland of dessicated industrial plants and unprofitable agricultural concerns”

…

“The further we went down this branch line to the coast, the more the sense grew that the past had been greater and busier than the present.”

“…for Boston’s swollen population, its high rents and house prices relative to other parts of Lincolnshire, and, for a time, it led to overcrowded doctors’ surgeries and schools.”

…

“when crowds are desperate enough”

De-Industrialisation

The first thing I observed is that the political events seem mostly to be rooted in large scale economic changes that have occurred over a relatively short time and which have similarities in many countries that previously were described as industrialised but whose economy is now difficult to describe in a single term. It seems to me particularly symptomatic of the analytical problem that in the days when I was teaching development studies in the 1970s we had no difficulty in characterizing western economies as industrialised and much of the development literature presented development as the process of industrialisation. The term “advanced economies” was also often used. Now these terms seem hardly adequate to describe these economies and we struggle to find alternatives. During the period of spurious economic growth based largely on rising debt that took place in the 1990s and accompanied de-industrialisation, the changes were described by politicians and the media in glowing terms as leading to the creation of information societies and new knowledge economies which were going to free us from economic booms and busts, bring about prosperity for all and solve all our social problems (see my articles Technological Determinism and Ideology: Questioning the Information Society and the Digital Divide and Creative East London in Historical Perspective). Now that those illusions have been shattered by the 2008 crash and the Great Recession there is no term to describe the societies or economies that we are living in. It seems to me that the most appropriate term to describe them is de-industrialised. The term is a negative one that fails to capture whatever centres of economic dynamism exist in these countries, and only captures the disappearance of particular economic activities, but it is perhaps the term that most clearly relates to the political phenomena that we are trying to explain 1 . This is a process that has devastated vast areas of many countries and their populations over a relatively short time- it started only in the mid-1970s. The quotes I reproduced above from the Guardian articles make references, both overt and implicit, to this. Even in Eastern European economies (including East Germany), the rise of the far-right is linked to de-industrialisation. The Soviet era industries were highly labour intensive and large swathes of people have been devastated by de-industrialisation. It seems to me that whilst de-industrialisation is a term that is often referred to in passing when describing its economic and social effects, it is a neglected term in analytical terms. It should be understood as representing well the effects on particular regions of the world of a historical stage of development of the global capitalist economy. De-industrialisation also killed the proletariat in Western economies as an economic force and as political agency in the way Marx conceived it, although the people whose culture was developed under the industrial economy haven’t all died yet. Some have become unemployed, others migrated to lower paid service occupations 2. They are still inappropriately being called the white working class because of their cultural characteristics even though this is no longer their economic function. They are not currently the main providers of profits for capital. They constitute a significant part of the audience of a far-right that looks backwards to a time when things were supposedly better. This is illustrated by the Guardian articles.

Mass Production of food along global food chains

Not all the economic changes that have been described in the articles are related to de-industrialisation, however. The case of Lincolnshire and East Anglia which forms the focus of Ian Jack’s article is different, but it too has echoes elsewhere. Here it is the effects of the development of the mass production of food supplying the oligopolised supermarkets feeding urban consumption- the supermarket chains that are at play. The region has become a centre for industrial packaging of food and agricultural produce imported from all over the world and for the mass production of indigenous food commodities with its requirement for seasonal labour. A typical example of this is graphically described by the Daily Mail here.The urban demand for cheap food fuels the pressure for low wages. The supermarket chains call the shots. Profits are mostly realised there, although largely generated in the plantations of the “Third World” 3 and in the fields and packaging factories of East Anglia and other areas of rural England. The indigenous population presumably had mostly migrated to higher paid jobs elsewhere, most likely London 4 . The demand for labour was met by immigrants who more than made up for the internal outward migration which was mostly of younger people. The remaining indigenous population has aged considerably, and the pro-Brexit vote reflected this fact5

Here is a quote from a local study of population trends:

“The proportion of young people in Lincolnshire (aged 0-19) has once again fallen from approximately 23 per cent of the total population in 2007 to 22 per cent in 2017. In contrast between 2007 and 2017 the population of those aged 65+ has increased in the county by 3 per cent to approximately 23 per cent. The two factors together highlight a declining younger population and a growing older population in the county.” Presumably these figures include the age profile of the immigrant population which will have skewed the pattern in the opposite direction as it is mostly young. (Source:www.research-lincs.org.uk/UI/…/Population%20Trends%20Lincolnshire%202017.pdf)

. .

In 2015, Boston’s non-British population was 16 times larger than it had been in 2005 (rising from 1000 in 2005 to 16,000 in 2015).

They are disenfranchised and were not allowed to vote in the Brexit referendum].

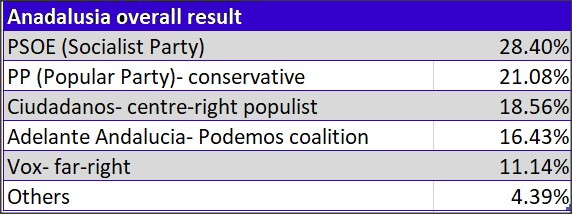

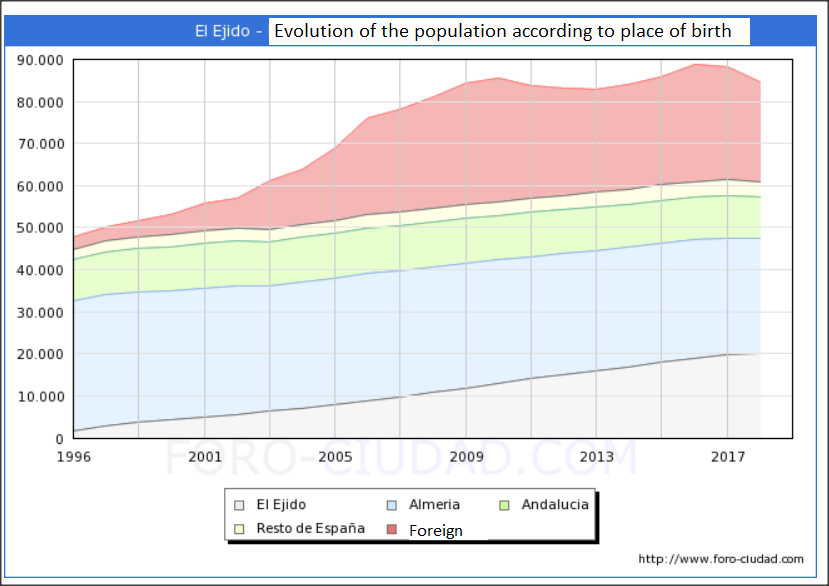

That the situation in East Anglia is mirrored elsewhere was brought to my attention by the rise of the far-right party Vox in the recent Andalusian regional elections in Spain. I have been puzzling about the fact that Spain and Portugal had been the only European countries where, until then, the far-right hadn’t raised its ugly head. Now the phenomenon was appearing in Spain also, so I tried to understand the Andalusian electoral phenomenon and I researched the social characteristics of the constituency where Vox had it highest vote, a higher vote than any of the other parties competing. I was going to use the words traditional parties, but this is inappropriate since both Podemos and Ciudadanos attracted large votes and are recent “populist” parties.

Here is what I found:

The town in Andalusia with the highest vote for the far-right Vox was El Ejido.

El Ejido

I investigated the nature of El Ejido, the town with the highest vote for Vox. Both the main national parties, the PP and the PSOE lost a significant part of their electorate to Vox in relation to previous elections.

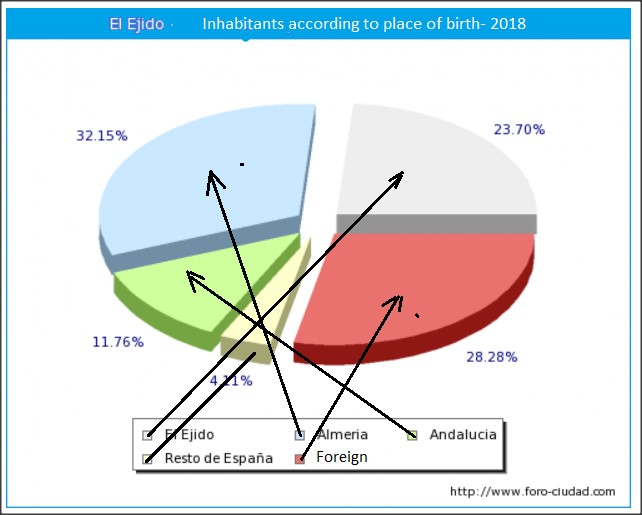

Here is a snapshot of El Ejido:

El Ejido is in the province of Almeria. Almeria is the area where the mass production of agricultural products is concentrated in a forest of polythene tunnels. Its economy has many similarities with East Anglia and Lincolnshire and with Boston in particular.

https://www.foro-ciudad.com/almeria/el-ejido/habitantes.html#Evolucion

The following is an extract from an article in the Spanish news site El Confidencial:

The pattern in the Ejido is clear: if things do not change much, this may be the first municipality in Spain to have a mayor from Vox. A city of 89,000 inhabitants with a 30% immigration in the hands of the far right would be an explosive cocktail. Only six months left for the municipal elections in May and the ejidenses, far from looking the other way, confirm that this was not a coincidence. Rocío, who runs a clothing store and says he votes socialist, claims that in this city there was a lot of frustration unexpressed. “They’re invading us. The number of immigrants has grown so much and they don’t stop arriving every day. People are tired of seeing how they give them all the help and seeing the crowded health centers. And if you go to the ER to the West Hospital the same, there is a tremendous queue and very few doctors. I will never vote to the far right, but what has happened does not surprise me. “

Inequality

“Most of the small towns, linked by winding and poorly paved roads, were the sort of places whose names caused metropolitan Slovaks to raise their eyebrows in consternation”.

…

“If the economy goes down the toilet,” he said, “at least those bastards [in London] will finally know what it feels like to be us.”

The growth of inequality has been widely recognised as a possible source of the problem. This is normally blamed by the centre-left on neoliberalism which has de-legitimised the state as the means by which the growth of inequality can be prevented. Inequality is normally thought of in terms of income but in these Guardian articles and associated stories it appears in multidimensional forms. The statement:

“If the economy goes down the toilet,” he said, “at least those bastards [in London] will finally know what it feels like to be us.”

expresses vividly several dimensions of the problem. Resentment against economic inequality but viewing it in geographical terms. The “bastards in London” is a term which would seem also to encompass a view of where the elites from whom he feels alienated are geographically located. I would argue that it also expresses the sense of alienation from the centre of power. It isn’t just, or even mainly, a matter of inequality of income. Ultimately it is about inequality in power, a feeling of powerlessness. Things are getting worse, and we have been the only ones to suffer. Ultimately it expresses also the feeling of lack of political representation by the politicians in London . I deal with this in the next section. The economic changes that I discussed in the previous sections have increased the economic gap between geographical areas. What growth there is almost exclusively concentrated in the very large cities. Smaller towns and rural areas have borne the brunt of de-industrialisation. A substantial increase in geographic economic inequality occurred over a relatively short time between areas which had a past that mattered because industry was located there when industry was central to the economy and the major metropoles. These became the sole centres of positive economic activity largely organised around consumption. Inequality didn’t increase in a context of a rising tide which lifted all boats, but some higher than the others. It was more a question of a question of substantial areas of the country experienced an ebb tide. Hence the “the high streets of boarded-up shops and pubs, full of payday loan outlets and bookies” and the “communities … destroyed as the manufacturing that had sustained them either folded or moved to low-wage economies” and even the “hinterland of dessicated industrial plants”.

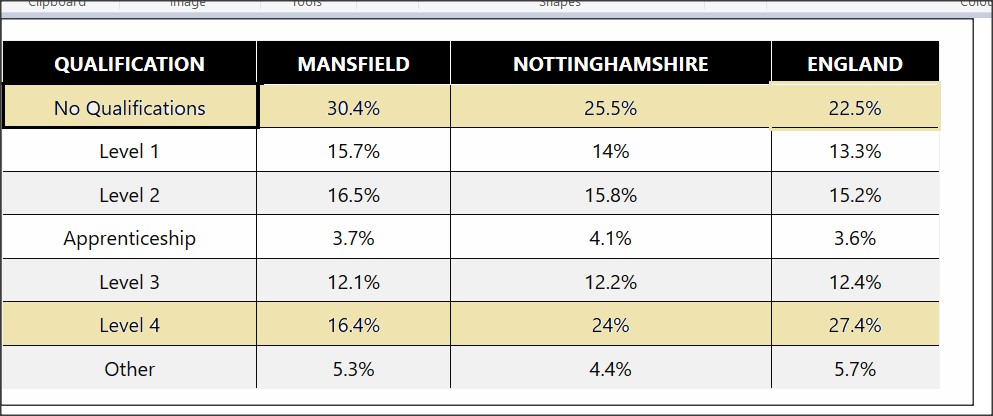

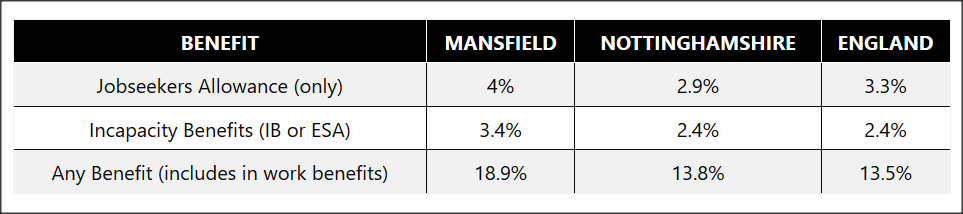

The sense of areas with a past but no future is compounded by the accompanying demographic changes. As the young migrated to seek a future elsewhere, those who were left behind were the old, the incapable and the unqualified. Although hardly a scientific, study I looked at two areas: Mansfield, at the centre of a Nottinghamshire mining area whose mines closed in the after the 1984 miners’ defeat, where 70.9% voted for Brexit, and London where 59.9% voted remain. Mansfield has 24.1% of the population of pensionable age compared with 10% for Inner London and 16% for Outer London.

The qualification profile of the working age population of Mansfield is:

The overall population of London fell between 1939 and 1991, but has grown rapidly since, by over 1 million in the two decades up to 2011. Currently 60% of the working-age population of Inner London and 45% of Outer London have degrees. However, among recent graduates there has been a sharp increase in graduates taking non-graduate jobs, particularly since the recession in 2008, rising to 47%. The educated bastards in London are taking jobs that previously might have been done by the less educated from Mansfield (Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-25002401)

The benefits profile of the population of Mansfield is given in the following table:

The large metropoles too had regions which had been victims of de-industrialisation, but many of these were the object of regeneration schemes such as the Liverpool, Tyneside and London dockland areas and, more recently, East London by hosting the Olympic games.

Thus, there is increasing geographic polarisation of the country between areas with a past which died and now have no future and areas which have acquired some dynamism particularly in the 1990s, albeit fictitious. This dynamism has stalled since 2008. The sense of dying areas and areas with a future is reflected not only in the physical infrastructure (rising skyscrapers peppering the skyline of London, boarded-up shops and pubs, full of payday loan outlets and bookies in the depressed areas) but also in the age profile of the population.

The crisis of representative democracy

“At the same time people around the world feel the pain of their broken dignity and are angry about having been deceived.”

“People in those former industrial towns spoke of their anger and betrayal, of having been forgotten by Westminster politicians”.

“a(n) … acute feeling that the Slovak political class was isolated from the masses and only interested in lining its pockets”

The articles point to a generalised popular disillusionment with representative democracy. Everywhere where this exists, large numbers of people, perhaps most people, feel that their interests aren’t being represented by those who have been elected and purport to be their political representatives. Governments and parliaments are regarded as part of a detached self-serving elite living in a bubble to which the majority have little or no access (e.g. a(n) … acute feeling that the Slovak political class was isolated from the masses and only interested in

lining its pockets).

These elites are considered to include all those who do not share this feeling and who make their focus the political shenanigans of representative democracy. They are geographically concentrated in metropolitan centres. In the UK the Guardian, the BBC and a significant proportion of their readers, viewers and listeners are prime examples. They appear to have little awareness of, and sympathy for, these feelings and devote little space to the discussion of the crisis of representative democracy. For them, democracy continues to be synonymous with political parties and elections, even when clearly a majority of the people don’t feel represented. Reference to its problems are mostly limited to discussions of the adequacy of different electoral systems. Yet, popular alienation from the electoral process seems to be well nigh universal and exists under all electoral systems.

Virtually all populist parties and movements, of the left (e.g. Syriza and Podemos, I would place Corbynism in this category, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez), of the right (too numerous to list and they now in government in the US, Italy, Poland, Hungary and others ), of the centre-right (Ciudadanos in Spain, Macron and En Marche in France, 5Star Movement in Italy) that have gained popular support have done so largely on the basis of distancing themselves from the traditional politicians and the elites, even when they are clearly members of the elite themselves.

This crisis of legitimate political representation presents perhaps the greatest danger. The fact that politicians who denounce the elites as being responsible for the people’s woes and claim to be able to make things better if they gain power are gaining traction electorally is particularly dangerous. If they gain power and fail to improve the economy, as is likely, the clamour for authoritarian solutions to deal with any resulting unrest will grow. This applies to left populism as well as the right. Watch events in Brazil.

Conclusions

The factors that underlie the common aspects of the political phenomena discussed in the articles are economic in nature. Even the crisis of representative democracy has economic roots- the corruption of politics by the money which funds political campaigns, corrupts politicians both outright and through the revolving door between elected politicians and big business.

They are the result of a sea change in the global economy which took place over a very short period and its stagnation since the 2008 Great Recession. De-industrialisation of the industrialised countries has occurred since the 1970s, a period of little more than 40 years whilst industrialisation took centuries to reach its zenith. The making of the industrial working class, which I have argued should now be referred to as the old working class, its communities and culture, took place over centuries. The culture and often the jobs were passed on from generation to generation. It was destroyed in the blinking of an eye. De-industrialisation of the Western countries has been accompanied by an equally rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of China and of what were called the tiger economies. It seems to me that speed of change needs to be factored into the analysis. Rapid change has disrupted in a short time the identities of individuals and communities which had taken a long time to form.

The term that has been used to capture all these changes has acquired popular currency is globalisation. But this obscures their fundamental cause, the result of the dynamics of capitalism, of a system whose main driver is the need to accumulate capital rather than responding to real human need. It is the irrationality of this system which produces the ecological and human abomination of a food system which results in the situation that exists in East Anglia, East Midlands and in Almeria and worse in the “Third World”. De-industrialisation was the result of a crisis of profitability for capital in the Western industrialised countries. To reacquire profitability a war on labour was unleashed on many fronts, including relocation of production to low wage countries, reorganisation of the labour process in production.

See my articles: The Death and Rebirth of Class War and |Class War in Historical Perspective

To blame globalisation and/or neoliberalism rather than capitalism, even by the Left, reflects the fact that the image of an alternative form of economy and society which used to be called socialism no longer plays any visible role in the public arena. This is even true in the case of Corbynism and of the various forms of left populism. Podemos in Spain is fighting for a “radical democracy”. Varoufakis is trying to build a movement for a “democratic Europe” as an alternative to Brexit. This amounts to general ideological acceptance of the “There Is No Alternative” thesis. It expresses the view that the best we can aim to do is to try to tame and ameliorate capitalism and to limit globalisation by strengthening the national state against global capital. This has serious nefarious political consequences as it leads to the confluence of economic policy proposals between the far-right and the left. Italy is prime example of this.

It is heartening that socialism and the language of class is making a reappearance in the most unlikely of places, US politics. To energise people it is necessary to create an image of the promised land, however distant it maybe. The political campaign being run by Bernie Sanders in which he creates the vision of what democratic socialism means to him, despite its considerable limitations, is a major advance on anything being done in Europe or anywhere else as far as I know. It should constitute an object lesson to Corbyn and Varoufakis. His statement that what he wants is not to become President but to head a movement for change towards democratic socialism is a sea change in the way politics is being conducted and will undoubtedly differentiate him from all the other candidates now coming forward to claim the progressive label. The new US left, where young political representatives of the new working class such Alexandra Ocasio Cortez are emerging, is providing object lessons on how progressive politics should be conducted. It includes a spirited defence of immigrants. This is almost totally absent from Europe where fear of the electoral alienation of what remains of the old working class has largely led to a hugely dangerous silence and ambivalence on this issue. Pointing to the real culprits, capital, for our woes is the means by which principled defence of immigrants can be conducted and unity of people across borders can be build.

Also see:

and

Bernie Sanders Is Running—and America Just Might Be Ready to Elect a Democratic Socialist –The Nation (19 Feb 2019)

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

14 March 2019

- At one point the term “service economies” was tried but fell into disuse to be replaced by the more enthusing “knowledge economy”. .

- In the UK we are about to enter a new wave of de-industrialisation as a result of Brexit as an industrial strategy based on attracting inward investment using the UK as the manufacturing base for the EU market crumbles. More of the little that remains of the industrial working class will lose its economic locus. .

- We struggle too to find an alternative descriptive term for these countries nowadays .

- On a quick search I have been unable to find any research to substantiate this. I have found out that internal migration patterns are hard to trace due to lack of suitable statistical data. .