In Part 2 of my blogposts on Black Lives Matter I raised the issue of the relationship between parliamentary and extra-parliamentary action in contributing to progressive democratic social change. I argued that most significant social change has been achieved by extra-parliamentary action pressurizing government and parliament to implement change rather than by parliamentarians initiating change. Improvements in the standard of living of ordinary people during the post-World Warr II economic boom have been mainly the result of the strength of the extra-parliamentary labour movement. Recent obscene increases in inequality have been made possible by the comprehensive defeat of that movement in the 1980s.

Recent explanations for increases in inequality and the rise of populism in politics advanced in the pages of the Guardian have ascribed the electoral appeal of the far-right to working class voters to the fact that traditional left parties abandoned them when they embraced neoliberalism during their Third Way phase. Thus, the politics of Blair in the UK and Clinton in the US, articulated theoretically as the Third Way by the sociologist Anthony Giddens, are said to be responsible for the current turn to populism by the (ex-)industrial working class. This is a theme first brought to widespread public attention by Thomas Frank in his successful 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?, published in the UK under the title What’s the Matter with America. In the aftermath of Trump’s defeat in the US presidential elections, in which Trump actually increased the number of his voters by more than 10 million, Frank reiterated his argument this month in the pages of the Guardian in an article entitled Ding-dong, the jerk is gone. But read this before you sing the Hallelujah Chorus. This has become virtually the orthodoxy amongst commentators in the Guardian and left-leaning liberal press. Julian Coman, an associate editor of the Guardian, restated it on 17 November in an article entitled Cummings should not be forgotten: Labour has to learn what he got right. At one point, he said

The association of Brexit with a reassertion of the values of working-class communities, neglected for decades, led eventually to the fall of the “red wall” seats last December. For Labour, the need to prevent that collapse becoming a historic realignment is existential.

In the London Review of Books, on the 19 November, Adam Satz picks up the same theme in relation to the US. He says

The weaknesses of American democracy, which the Trump presidency has so powerfully exposed, can’t be entirely blamed on the constitution or on political procedure. They are rooted in the defeat of Reconstruction after the Civil War and the enduring power of white supremacy. In recent years, they have been amplified by deindustrialisation, the collapse of organised labour and the rise of social media. The Democratic Party bears a share of the responsibility for this. Since the Clinton administration, it has prioritised free trade and globalisation over jobs and economic equality, becoming a party of college-educated middle-class professionals, and largely turning its back on working-class voters.

This argument is undoubtedly correct. It has recently been adopted by what may be called the left political establishment who are committed to politics being conducted on the centre ground. In the UK, it has also been adopted as a central political argument by the Tories to gain electoral support in de-industrialised areas of Britain, the so-called “red wall” seats. The issue has underpinned a strange alliance between the Tory right and the Labour Party centrists to denounce Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. A Daily Express headline to an article reporting on an opinion poll predicting widespread loss of “red wall” seats in the 2019 referred to ‘The abandoned northern heartlands where Corbyn is losing votes’.

Is democracy synonymous with representative democracy?

There is, however, a fundamental contradiction in the position of the Labour Party right-wingers and centrists who are now using this argument to attack the Corbyn leadership. That contradiction is generated by their hostility to extra-parliamentary politics and the restriction of the concept of democracy to that of parliamentary democracy. At the time the working class was desperately fighting in the 1970s and the 1980s to defend their communities, their standard of living and prevent de-industrialisation, the ‘moderates’ in the Labour Party, the right wing and centrists, were notorious for their absence from the struggle. They also denounced those fighting in the factories and the mines as extremist militants who would ruin the Party’s chances at polls. The height of the struggles to preserve the standard of living under attack by the Labour Government of James Callaghan came in the 1979 so-called Winter of Discontent wave of strikes. This was (correctly) denounced by the Labour Party leadership and by the Guardian as responsible for causing the loss of the 1979 election. Soon after the election, the Guardian expressed its view that the extra-parliamentary defence of workers’ living standards was a threat to democracy. In an editorial entitled “An unhappy band of brothers” attacking the role of trade unions, published soon after the 1979 election, the Guardian stated

‘however strong or honourable your claim, democracy comes first. The people of Britain, for their various reasons, have elected a Conservative government. That Government has specific policies, some sensible, some less so, for redefining the role of the unions. If relatively modest statements of intent by Ministers are immediately defined as declarations of war, that will diminish, not enhance, the merits of the union case in the eyes of many fair minded people.’ (The Guardian, 26 May 1979).

Another Guardian editorial, published on 3 September 1979, entitled “Why the TUC must say more than No”, returns to the attack on organised labour’s use of the strike weapon, implying that it was responsible for alienating the public from the Labour Party. Its message was that organised labour had been too strong and had defeated the various legislative attempts by Harold Wilson’s government to bring it under control, thus opening the door to Mrs. Thatcher’s win in the May 1979 general elections. The depth of the Guardian’s feeling was expressed in the ironic phrase ‘After all the TUC’s record of destruction over the past decade has been impressive’2(The Guardian, 3 September 1980). In September 1979, in what the Guardian’s then political correspondent, later political editor, Michael White’s report described as a major speech, Denis Healey said that “Labour was defeated in May not because our policy was Right Wing … but because of the winter’s strikes which destroyed Labour’s greatest political asset- the cooperation between the Government and the TUC”. (The Guardian, 10 September 1979)

In 1984, British coal miners fought their final losing battle for their jobs. This effectively became the swan song for a British organised labour movement capable of defending the living standards of workers and ordinary people. They confronted the vicious attack of the Thatcher Government using the full force of the state repressive apparatus which culminated in their defeat in the Battle of Orgreave. The Labour Party establishment held an equivocal position during the strike, accusing the miners of extremism and decrying their violent tactics. Following the miners’ defeat, NUM President Arthur Scargill, who had led that battle, became the object of scorn and vilification by the Labour Party centrist and right-wing establishment in a campaign which has recently been echoed in the demonisation of Jeremy Corbyn. This was faithfully mirrored in the pages of the Guardian. At the first Labour Party conference following the defeat of the miners, in October 1985, Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock rounded on Scargill with passion. The following day, leading Guardian columnist Hugo Young3 cheered Kinnock’s courage but berated him for not having denounced Scargill during the strike.

Young described Kinnock as having

‘stood erect, white faced, positively gaunt in his apparent disdain for that half of the people in front of him who had first cheered Scargill to the echo. He spoke with few notes and unbroken fluency, and for once he did not fill even a particle of the air with empty vapouring’. Furthermore, ‘his unbridled sarcasm was hugely offensive and hugely effective…Never in living memory has the leader of any party spent so much time being unemollient to the assembled ranks of his supporters… If leadership consists of rallying the waverers and putting heart into those who feel they have lived for years with their backs against the wall, the Labour Party has a leader.’ (The Guardian, 3 October 1985)

The underlying argument used against the miners and Scargill by the establishment was again that they had put the electoral chances of the Labour Party in jeopardy by their militancy.

Kinnock’s 1985 conference speech started the journey that eventually led to the development of Third Way politics and Blairism, currently being held responsible for the loss of Labour Party parliamentary seats in previously industrial areas. There is also a general consensus that the rise of populist politics has been triggered by the huge increase in inequality that has developed since then.

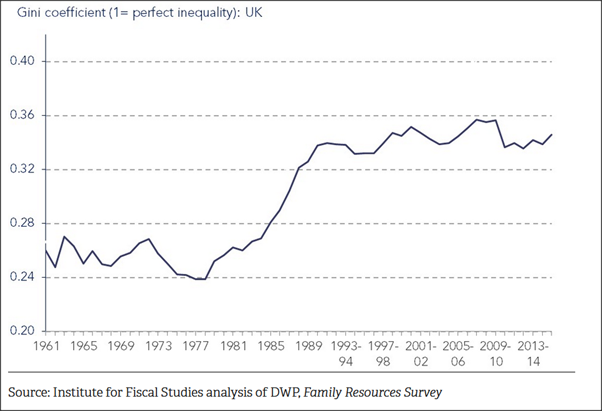

The graph below showing the evolution of the Gini index measure of inequality clearly demonstrates that the greatest decrease in inequality occurred in the early 1970s at the time when labour militancy defending its gains under attack was at its greatest. Inequality increased hugely following its defeat in the Winter of Discontent which ushered in the Thatcher era, and accelerated after the defeat of the miners 1985 strike.

It is interesting to note that this militancy did not always affect Labour’s electoral prospects negatively. In the 1972 strike, coal miners had a major victory picketing a power station at the Battle of Saltley Gates. Following this, and his institution of the three day week, Prime Minister Edward Heath called a general election in 1974 with the slogan ‘Who rules the country’ seeking a mandate to move against the unions. He lost. It may therefore be that it is the defeat of the organised labour movement rather than its militancy that affected negatively the electoral prospects of the Labour Party.

Conclusion

The notion that democracy is synonymous parliamentary democracy is an integral part of capitalist ideology. It removes any economic dimension from the concept and therefore hides from view the issue of class and class power relations. Economic inequality thus becomes acceptable and never viewed as a threat to democracy. In this ideology, politics is largely reduced to parliamentary activities as the only legitimate expression of democracy. It removes from public view any structural power relations and practices by capitalists that are necessary for the operation capitalism as a system of rule which might otherwise be considered undemocratic. As an example, we could think about practices at work. That workers have no say in the running of the enterprise they work in isn’t considered undemocratic. Management’s right to manage is internalised as an immutable law of nature. Similarly, women or black people being treated as second class citizens isn’t an affront to democracy. It is merely, at most, somewhat unfair.

The internalisation of this ideology by “the establishment”, the elites that create the rules of parliamentary politics, is what leads to a language of politics that divides political actors entirely into the two categories of “moderates” and “extremists”. The moderates are those that are willing to operate within those rules. They deny legitimacy to extra-parliamentary movements even when it is clear that parliament and government are impotent to deliver economic and social democracy and fairness.4 Kinnock’s attack on Scargill on the grounds that he was jeopardising the electoral chances of the Labour Party was vehemently applauded by the Guardian’s Hugo Young . The miners’ extra-parliamentary defence of their livelihood and their communities was considered undemocratic. At the time, the Guardian’s editorial position decried the violence “by both sides” at Orgreave. It considered both sides had behaved as extremists.

In 2016, more than thirty years on, the Guardian changed its stance. On 31 Oct 2016, it ran an editorial which stated that ‘there is copious evidence that the police at the least mislaid the rule book in their attempt to break the miners’ strike’. This is part of the process of revising its version of history without examining its own role in it. This is currently informing the new consensus with which I started this blog post that the Labour Party’s loss of the so called “red-wall” seats has been caused by its having abandoned those communities in the Blairite years. The Guardian at the time was a cheerleader for Blair and applauded his acceptance of the main propositions of neoliberal ideology5

The basis of this support was that the ideological reconstruction of the Labour Party abandoning any reference to the concept of socialism was necessary to win elections. In this both Blair and the Guardian were correct.

Here lies the weakness of Thomas Franks’ critique of Third Way politics. Frank, and the other authors I quoted at the beginning of this post, argue that electoral loss today is the coming home to roost of the historic betrayal of these communities.

But Blair and Clinton demonstrated that the betrayal was necessary to win elections then. There is little doubt that if Tony Benn, who supported the struggles of the industrial working class against de-industrialisation, had led the Labour Party instead of Blair, the Party would have experienced an even worse electoral defeat than it did under Michael Foot.

The reason for this may be that the public knows that economic power lies in the hands of capital. Any election which will lead to the government challenging the fundamental interests of capitalists will result instantly in a major economic crisis as capital goes on strike, or moves elsewhere to seek the profits it cannot get in the country.

At this point we could stop to ponder on another aspect of this ideology. The extra-parliamentary struggles of workers to defend their livelihoods and their communities are portrayed as a threat to democracy, as are the street battles of the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet, the extra-parliamentary activities of capital, such as the movement of the stock exchange share prices, or the movement of capital to where it can obtain the highest profit, leaving devastated communities behind, are viewed as a fact of life, legitimate activities which politics must take in its stride.

Bowing to the vital interests of capital is the inevitable political reality for centre-left parties operating in accordance with the ideological rules if the objective is to win elections rather than to struggle to construct a fair and democratic society, including in its economic dimension.

Whilst the capitalist economy is growing, the system can maintain a degree of social cohesion insofar as standards of living are rising and the state is able to guarantee a minimum of equity so that few feel left behind. Also, when there is full employment, labour is relatively strong, able to demand a share of growth and to partially confront the extra-parliamentary machinations of capital. When the economy hits the buffers, the economic mechanisms that enable social cohesion to be established break down. Populist feeling is the result of this, not its cause. I have discussed this process in some detail my recent Soundings article entitled ‘Class and nation in the age of populism’.

Also, governments tend to get blamed for the economic crisis which they have had little power to create and even less to resolve. This is increasingly the case as the globalisation of capital has proceeded. The capitalist economy has its own dynamic largely dictated, as Marx analysed more than 150 years ago, by the relationship between capital and labour. It is an illusion, however, that national sovereignty will enable social cohesion to be re-established based on the defence of the ‘national interest’. That’s not what capital wants. Boris Johnson is about to find this out to his and everyone’s cost.

I have implied that the Guardian ends up reflecting the voice of power, rather than speaking the truth to power. However, as befits a liberal newspaper, in a policy that still holds today, occasionally the views of the victims are reflected in its pages. Whilst researching for this post, I came across an article in the paper by Peter Jenkins which movingly describes what the miners were fighting for in their own words. Jenkins wrote:

‘What the government calls economics offends against what these miners call morality. The moral assumptions of Thatcherism are utterly repugnant to them. Working underground it seems self-evident to them that life is about mutual dependence. They set no store by economic individualism… The productivity bonus scheme is offensive to them because- they quote Scargill- “it sets men against men”. Bill thinks it right that low cost pits should help the others… The president of the branch, Tony, tried to sum up what it was they were fighting for. “it’s such a broad issue he said. “It’s like chucking a stone in a pond and the ripples spreading. You’re fighting for your pit first of all. But you’re fighting for your village and your kid’s future…’ (The Guardian, 19 December 1984)

But you have to dig deep in its columns to find the voice of the victims or of the dispossessed. This is something that its own commentator Aditya Chakrabortty recognised last year in his comment column entitled Britain’s real democratic crisis? The broken link between voters and MPs:

That vast disconnect between elite authority and lived experience is central to what’s broken in Britain today. Why is a stalemate among 650 MPs a matter for such concern, yet the slow, grinding extinction of mining communities and light-industrial suburbs passed over in silence? Why does May’s wretched career cover the first 16 pages of a Sunday paper while a Torbay woman told by her council that she can “manage being homeless”, and even sleeping rough, is granted a few inches downpage in a few of the worthies? Oh, some may say, they have no connection. Except that the death sentence handed to stretches of the country and the vindictive spending cuts imposed by the former chancellor George Osborne are a large part of why Britain voted for Brexit in the first place.

In the circumstances, the current concern about the plight of the left behind communities feels a little like crocodile tears…

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

10 December 2020

[1] I have argued that it was indeed a declaration of war in my article ‘Class War in Post-World War II Historical Perspective’.

[2] The Guardian’s attack on the TUC was somewhat unfair since it had been reluctantly forced to act in defence of labour by spontaneous rank and file action led by shop stewards. The TUC leadership was deeply reluctant to lose the opportunity of regularly sharing beer and sandwiches with members of the government in 10 Downing Street. Under Thatcher’s government they were no longer welcome. Thatcher saw no need to keep them on board.

[3] Hugo Young became the Chairman of the Scott Trust, owners of the Guardian, in 1989. After his death in 2003, the paper honoured his memory by instituting the annual Hugo Young lecture series which has been delivered by David Cameron, Nick Clegg, Ed Miliband, Marjorie Scardino and Alex Salmond amongst others.

[5] Hugo Young hailed Blair’s 1997 general election victory with the words:

“Blair has principles and objectives, a mix of hard-headed idealism, that deserve the trust the country has so massively placed in him. After years in which the concept of political leadership was first defiled by manic arrogance, and then by posturing timidity, Britain now has given itself the chance to experience something quite different from either model”. (The Guardian, 2 May 1997)

I have argued that it was indeed a declaration of war in my article ‘Class War in Post-World War II Historical Perspective’. ↩

The Guardian’s attack on the TUC was somewhat unfair since it had been reluctantly forced to act in defence of labour by spontaneous rank and file action led by shop stewards. The TUC leadership was deeply reluctant to lose the opportunity of regularly sharing beer and sandwiches with members of the government in 10 Downing Street. Under Thatcher’s government they were no longer welcome. Thatcher saw no need to keep them on board. ↩

Hugo Young became the Chairman of the Scott Trust, owners of the Guardian, in 1989. After his death in 2003, the paper honoured his memory by instituting the annual Hugo Young lecture series which has been delivered by David Cameron, Nick Clegg, Ed Miliband, Marjorie Scardino and Alex Salmond amongst others. ↩

The current contortions of the football establishment, bounced into accepting the bended knee salute as a symbolic protest against racism by the Black Lives Matter movement, now trying to extricate itself from any association with that movement is graphic example of the syndrome ↩

-

Hugo Young hailed Blair’s 1997 general election victory with the words:

“Blair has principles and objectives, a mix of hard-headed idealism, that deserve the trust the country has so massively placed in him. After years in which the concept of political leadership was first defiled by manic arrogance, and then by posturing timidity, Britain now has given itself the chance to experience something quite different from either model”. (The Guardian, 2 May 1997) ↩