Introduction

I am part of a WhatsApp group of Portuguese tracking the electoral rise of the far right and trying to understand the reasons for it. It started as a response to the sudden appearance of the new far right party Chega on the electoral scene when its leader, André Ventura, came third in the 2021 Portuguese presidential election. I wrote about this event in my blog post Reflections on the Recent Presidential Elections in Portugal and the Rise of the Far Right.

I posted recently in the group an alert about the sudden surge in support for the far-right AfD in Germany of which I had become aware as a result of reading a Financial Times article. I posted the following quote from the FT:

Germany’s opposition leader faces tough times. Merz’s goal of becoming chancellor fades as voters switch to far-right rival party. Friedrich Merz, leader of the German opposition, should be basking in skyhigh approval ratings and positioning himself as his country’s chancellor-in-waiting. In theory, at least. Instead, he is watching in disbelief as voters dissatisfied with Olaf Scholz’s government increasingly plump for the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), now the country’s second-most popular party.

Merz’s Christian Democratic Union has fallen in the polls, just as the AfD — buoyed by inflation, recession, anxiety about the war in Ukraine and the government’s confused climate policies — is experiencing a surge in support

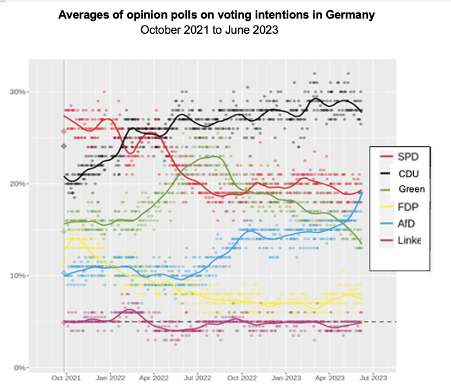

A member of the group then came up with a graph of voting intention trends as measured by opinion polls

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_for_the_next_German_federal_election

The discussion that followed drew attention to the very rapid rise in the voting intentions for the AfD over a very short time, from 10% in July 2022 to 19% in June 2023. It is now on a par with the Social Democrats (SPD). The parallel steep decline in voting intentions for the Greens, from 23% in June 2022 to 14% in June 2023, also stands out. The question that we raised was whether there was a direct link between the two trends, a direct transfer of votes from the Greens to the AfD. This would be somewhat surprising.

We also noted the preceding steep rise in the Green voting intentions from 16% in March 2022 to 23% in July 2022, apparently at the expense of the SPD which had a similar decline in voting intentions in the period. What might have caused these trends? We investigated this further and arrived at the following hypotheses.

The steep rise of the Greens in the first half of 2022 seems to have been caused by a popular revulsion against the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. An article we found in the Guardian says

Since taking office as part of Olaf Scholz’s three-party “traffic light” coalition government last December, however, Die Grünen have become the Bundestag’s most vocal advocates of supporting the Ukrainian resistance with heavy weapons. They have extended the running time of three nuclear power stations due to shut down at the end of the year, reactivated mothballed coal plants and built the country’s first terminals for importing fossil fuel in liquefied form. More surprisingly still, voters seem to like it. (My emphasis).

Another Guardian article explains why it might have taken place at the expense of the SPD:

Germany’s new chancellor Olaf Scholz is waving goodbye to the honeymoon period of his tenure, as his “inaudible” stance over the brewing crisis on the Ukrainian border is failing to impress not just Russia-hawks abroad but also more ambivalent voters at home.

Scholz, whose liberal-left “traffic light” coalition was sworn in less than two months ago, has been criticised by Kyiv and other east-central European capitals for sticking to his country’s restrictive stance on weapons export to crisis regions and looking slow to spell out the potential sanctions that could be triggered by a Russian invasion into Ukraine.

So it seemed that after the Russian invasion, the sympathy of Germans for the cause of Ukraine led to rise in their support for the Greens at the expense of their SPD coalition partners. However, the question remained as to why after July 2022 the Green voting intentions should have started to nosedive and those of the AfD to rise steeply.

Why do Germans vote for the AfD?

We first investigated the basis of the AfD vote in Germany. It has been well publicised that the AfD has found fertile ground in what was East Germany. This area has been a particular victim of de-industrialisation as the old Soviet era industries folded. We found an informative article in the Spanish newspaper El País,dated June 20, describing the situation in the eastern German city of Sonnenberg, not far from the Polish border, where opinion polls were predicting the AfD would win the elections to be held last Sunday, 25 June.

The article described a situation in the city very similar to those in the various parts of Europe that have voted for far-right parties that I have I been following in this blog. Those who have been ‘left behind’ by de-industrialisation, in areas of declining, aging population and deteriorating public services have been attracted to the far-right since 2009. The population of Sonnenberg declined by 24% between 1990 and 2015. The population of Germany as whole increased by 2.2% in the same period, and that of Frankfurt, the nearest large city, increased by 14%.

As to why the city would be voting for the AfD, the article says

Above all, one word is heard in the center of the town …: “discontent.” It’s the first thing that social worker Anja May, 54, mentions when asked why her neighbors have voted en masse for the AfD. “Money is scarce – they see that it’s not used for what it should be used for: education, nurseries, care for the elderly. People are fed up with [the government] and everything they’re doing wrong in Berlin,” she says.

Another person was asked the same question

She’s 25-years-old and assures this newspaper that “there’s nothing for German citizens – you work and work and the end of the month comes and you have no money left. There are more and more foreigners. I have nothing against them, but our country gives them everything for free. You see them with new cell phones, new shoes… very chic, they go out to eat here and there.”

The main selling point of the AfD is its stance as an anti-immigrant, Germans first, party. The election took place last Sunday and the AfD has won it, sending a shock wave through the German and European political scene. The election result was reported in the Guardian thus

‘Far-right AfD wins local election in ‘watershed moment’ for German politics’

However, none of this explained why support for the AfD should have begun to increase steeply since the beginning of 2022, as the opinion polls graphs show, and why the change should have come at the expense of the Greens. We investigated the hypothesis that it might have something to do with changing attitudes to the continuing war in Ukraine. We started by trying to find out what the impact of the war has been on the German economy.

The impact of the Ukraine war on the German economy

An article I had recently read in the Financial Times, ‘Europe has fallen behind America and the gap is growing’, had painted a grim picture the impact of the war on Europe as a whole, arguing that it had caused the gap between Europe and the United States to widen considerably. Amongst other things, the article pointed out that

‘The Ukraine war and the loss of cheap Russian gas mean that European industry typically pays three or four times as much for energy as their American competitors.”

Germany was particularly dependent on Russian gas, so it was likely that it would have suffered particularly badly. We investigated further. We found an article in an interesting English language online paper called The Local with the title ‘What impact has a year of war in Ukraine had on Germany’s economy?’ . The introductory paragraph stated

‘Experts estimate that the war in Ukraine cost the German economy €100 billion and made most people €2000 poorer in 2022. But big businesses and the defence industry saw profits rise.’

So, it seemed likely that most Germans might have come to change their views on the Ukraine war after their initial outrage at the Russian invasion as a result of economic hardship. We tried to find out what the AfD position on the Ukraine war had been. An article in Time magazine entitled ‘The War in Ukraine Is Emboldening Germany’s Far Right’ describes the growing movement in Germany against the economic effects of the war in which the AfD has played a significant role. It describes regular demonstrations have been held in the small eastern German city of Zittau. At one point the article states

While the protests began in 2020 over COVID-19 lockdowns, they have swelled in recent months as anger mounts in Germany amid the economic fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Alternative for Germany, a far-right party, is a regular fixture at these demonstrations. The party has opposed arming Ukraine or sanctioning Russia—a position that is resonating with some voters as the AfD polls at near-record levels nationally and looks poised to come first in some state elections in 2024.

Explaining the poll trends

Thus, it seems likely that the Greens’ enthusiasm for supporting Ukraine militarily gave the party an initial boost in the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion, but it eventually backfired to the relative benefit of the AfD. We have been unable to establish conclusively whether there was a direct transfer of votes, but this seems unlikely.

The core of the Green vote in Germany lies in the West and, in particular, in the main cities. It seems likely therefore that this is where the Greens gained their biggest surge in support 2021 after the start of the Ukraine invasion in January 2021, at the expense of the SPD and then lost this support from August 2022. It is likely that its support transferred mainly back to the SPD, halting the steep decline the party had experienced in 2022, but also to the CDU which has been gaining ground throughout the period of SPD-led coalition government. The AfD has little support in the large cities. Its support is mostly in the East of the country and in the smaller cities and towns in decline. It is likely that its increase in vote came mostly in these areas, probably at the expense of the SPD and the ex-communist and far-left, the Die Linke party. In Sonnenberg, Die Linke was probably the big loser as it was the party with the highest vote in the 2019 state elections with 28.1%. The AfD and CDU came a close second on 27.3% and the CDU had 27.1%.

Conclusion

The victory of the AfD in Sonnenberg appears to fit the general pattern I have been identifying in this blog as the revolt of the ‘left behind’, the victims of the global restructuring since 1980 of the world capitalist economy and its more recent stagnation. They have also borne the brunt of austerity policies instituted after the 2007/8 financial crisis which have led to an acceleration in the deterioration of public services.

However, the revolt appears to have been stoked in Germany by the peculiar effects of the Ukraine war on the country’s economy. The Greens, the German party that somewhat surprisingly was the most aggressive in its support for Ukraine, including advocating the sending of heavy weapons to Zelensky’s troops, initially saw a large surge in its support because of popular revulsion at the Russian invasion. However, the war has dragged on and appears to have exacted a heavy toll on the German economy which ordinary Germans have borne. As The Local put it, on average Germans are 2000 euros worse off since the beginning of the war whilst big business has reaped bumper profits. The Germans’ initial support for Zelensky has waned and the AfD has been the major beneficiary at the expense of the Greens.

Our analysis has also highlighted the impact that the war has had on the relationship between Europe and the United States. As a result of it, the hegemony of the United States over the Western alliance has been re-established. It has also contributed significantly to an increase in the economic gap between Europe and the United States. Europe has borne the brunt of the war. This confirms for me what I have always believed, that the expansion eastwards of NATO was driven by the United States out of a concern that the fall of the Soviet Union would remove the glue that kept the Western Alliance together and its hegemony over it. Another bogeyman was necessary to replace that of the Soviet Union.

I have written this blog post in this somewhat convoluted way to make visible the collective process of knowledge creation that was behind it in order to advertise and recommend it. However, the conclusions are entirely my own and are in no way meant to represent a collective view.

Post Script

This week’s shocking news of a capital city of a German state being governed by a far-right mayor needs to be understood in context of a general trend in Europe that appears to be accelerating. The shock of Georgia Meloni of the neo-fascist Fratelli di Italia becoming prime minister of Italy appears to have subsided and Georgia Meloni has been integrated into the mainstream of Italian and world politics, including being feted at the recent G7 meeting. Biden embraced her at the meeting. Earlier this month, the anti-immigration Finns Party became a member of a four-party coalition to rule in Finland, and in September the far-right populist Sweden Democrats won more than 20% of the vote and became the country’s second-biggest party. In Greece, in last weekend’s general elections, far-right parties won almost 13% of the national vote. A new neo-fascist party led by Ilias Kasidiaris won enough votes to gain representation in parliament. Kasidiaris is serving a 13-year jail sentence for his part in Golden Dawn’s criminal activities, which included acts of violence against migrants and political rivals All this is graphically described here.

Our recent discussion also led to the discovery of a recent opinion poll in France that showed that if French presidential elections were held now with the same candidates as last time, Marine Le Pen would top the poll with 32% to Macron’s 23%.

Our WhatsApp group has also been following the political landscape in Spain and Portugal. Spain is due to have general elections on 23 July next. It is currently being governed by a coalition of the Socialist Party with the far-left Podemos, as none of the traditional centrist parties can gather enough votes to govern alone. The relative collapse of the centre has been accompanied by a rise in the election fortunes of far-left and far-right parties. The far-left Podemos entered the coalition but has been losing electoral support in an increasingly divided far-left field. However, Yolanda Diaz, the current Minister of Transport and Second Vice-President of the government, appointed with the support of Podemos, has gained considerable national popularity and launched a far-left unity project under the title of Sumar. Diaz managed in the last fortnight to establish an electoral pact with Podemos under her leadership. PSOE Prime Minister Sanchez welcomed the pact and has said that he expects to be governing with Yolanda Diaz after the elections, although no formal electoral agreement has been reached. On the right, the traditional dominant centre right party, Partido Popular (PP), has entered 140 local government coalitions with the surging far-right Vox. Current opinion polls are predicting a PP victory but without an overall majority, thus creating the prospect of Santiago Abascal, the leader of Vox, becoming Deputy Prime Minister.

Portugal, the European country which had avoided the rise of the far right for longest, has a political situation not dissimilar from that of Spain. Before the last elections, Antonio Costa of the Socialist Party (PS) had governed with the tacit support of the far-left Left Bloc (BE) and Communist Party (PC). At the last elections, the PS gained enough votes to govern alone. However, on the right, the rise of the far-right and anti-immigrant Chega has forced the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD)1 to adapt accordingly. In the area where I grew up, the Azores islands, the PSD currently governs with the tacit support of Chega, adapting its own to Chega’s policies.

What all this demonstrates is the increasing polarisation of European politics, with the relative collapse of the centre ground, a trend much deprecated by the establishment. In the process, the centre parties are being forced towards the extremes in order not to lose even more votes. This is a trend Keir Starmer might do well to note. However, my analysis demonstrates that this trend is common across Europe and is driven largely by the failure of the established parties to respond to the needs of ordinary people, allowing the development of huge inequalities and the deterioration of essential public services, particularly in peripheral areas. This, in turn, has been forced on the parties by the workings of the capitalist economy as much at the global as at the national level. Austerity was a European-wide phenomenon brought about by the 2007/8 world financial crisis.

It puzzles me greatly that, when this seems so clear, politics continues to be analysed largely as a national phenomenon.

Alvaro de Miranda

28 June 2023

In the immediate aftermath of the April 1974 revolution no party dared to create a title for itself without the word ‘social’ it it. ↩