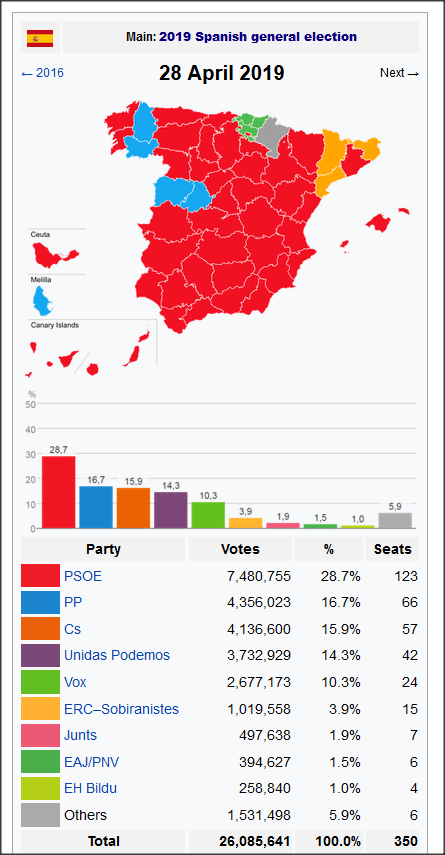

Spain held general elections on April 28 called by the Socialist Party (PSOE) leader Pedro Sánchez. Sánchez had been leading a minority government after the previous prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, leader of the main right-wing party, the Partido Popular (PP), had been defeated in a confidence vote in parliament on 25 May 2018 as a result of a major corruption scandal known as the Gurtel Case. The results were:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Results_breakdown_of_the_2019_Spanish_general_election_(Congress)

The main features of these results were:

- A major recovery for the PSOE, mainly at the expense of the radical left Podemos party and its allies. Podemos has been characterized by mainstream politicians and commentators as a left populist party and had previously been rapidly gaining support at the expense of the PSOE. In the 2016 general elections it had set itself the target of overtaking the PSOE and only narrowly failed to do so (Fig.2 below). In the current elections the PSOE obtained 28.7% of the votes and gained an additional 38 seats; Podemos and allies, fighting the elections as Unidas Podemos, lost 29 seats, obtaining 14.3% of the vote.

- The main right-wing Partido Popular (PP) suffered a major defeat. It received 16.7% of the votes and lost 71 seats. The main winners from the PP’s losses were the recent upstart centre-right Ciudadanos 1 which gained 25 seats and obtained 15.9% and the new far-right Spanish nationalist party Vox which entered parliament for the first time, winning 24 seats and 10.3% of the vote.

- With the rise of Vox, Spain for the first time in a national election sees the appearance of a significant far-right party. Portugal is now the only country in Europe without a far-right party represented in Parliament.

- Sánchez is to form the new government but doesn’t have an overall majority and will need the support of Podemos and of some of the nationalist parties of the Basque Country and Catalonia. A centre ground coalition between the PSOE and Ciudadanos would have been possible but has been decisively rejected by both the party leaders and, most vehemently, by the PSOE membership. Spain will be governed by a social democratic government which has rejected the Third Way and Blairism. This government will have strong similarities with António Costa’s government in Portugal and will have affinities with Siriza’s government in Greece. It will also be potentially a natural ally for Corbyn’s Labour Party, a situation which will be complicated by Brexit.

Understanding the results

The results exhibit several features that are specifically Spanish in nature. These have mostly to do with the importance of Basque and Catalan nationalism in Spanish politics and, in particular, the political fallout from the recent crisis created by the unilateral declaration of independence taken by the Catalan parliament in October 2017. However, many other features have much in common with trends elsewhere and these are the ones I will concentrate on. They reinforce themes I have been pursuing in recent blogs in seeking to understand the relative role that the concepts of nation and class play in the formation of identity and in the way that people vote.

The first aspect that should be highlighted is that the PSOE’s gains have been the result of its recent definite shift to the left led by Sánchez after a bitter struggle with what might be described as the Blairite wing of the party which previously dominated it and which had made its peace with neo-liberalism. Sánchez spent a period in the political wilderness. He had resigned from the position of Secretary-General as a result of the decision of the majority of the previous PSOE leadership to allow Rajoy to form a minority government following the inconclusive results of the 2016 Spanish general elections on the grounds that they were serving the national interest. He fought his way to win back the position with the support of the rank and file when new party elections for the post were held in June 2017. Since then he has succeeded in largely marginalising the internal Blairite opposition.

This mirrors in many ways the events that had previously taken place in Portugal when the current prime minister António Costa succeeded in getting elected to the leadership of the Socialist Party on an anti-Blairite platform. Costa challenged and defeated the then leader António Seguro in November 2014. He then led the party in the Portuguese general elections of October 2015 against the centre-right government party, misnamed Social Democratic Party (PSD). Costa won less votes than the PSD which had gained the most votes but failed to win an overall majority. However, he decided to form a government with the support of the parties to the left of his party, the Communist Party (PC) and the radical Left Block (BE), which together had obtained nearly 20% of the vote. There was considerable opposition to this alliance with the far-left within the Socialist Party but Costa prevailed and, against most predictions, has maintained in power a centre-left government that has gradually reversed several previous economic austerity measures, and introduced educational reforms which removed targets and prioritised cooperation with the teaching profession.

This process of decisive shifts of social democratic parties which had previously absorbed Third Way ideology to the Left in Portugal and Spain under the challenge of growing popular support for parties further to their left was preceded by events in Greece where the radical left party Syriza overtook the traditional social democratic party PASOK as a result of the economic crisis and eventually became the party of government.

The accession of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of the British Labour Party can also be viewed as part of a similar trend. The fact that in the UK the shift to the left under pressure from below occurred entirely within the Labour Party rather than through the rise of parties to its left is most likely due to the peculiarity of the British first-past-the-post electoral system.

Another parallel can be made. I have drawn attention to the sense of crisis that has overcome what I have called the “party of order” as a result of the seismic political changes that have occurred since the 2008 economic crisis. The “party of order” includes all those wedded to consensus “business as usual” politics and to the idea that elections must be fought and won on the centre ground. The European newspapers which regard themselves as centre-left “quality newspapers” in several European countries are prime representatives of the “party of order” and have been greatly upset by the political polarisation that has occurred. They have made strenuous efforts to try to ensure that politics returns to “business as usual”, by systematically attacking new developments on both the right and the left which are presented as equally damaging and the product of a nefarious political development called “populism”. This is reflected in the Guardian in the systematic and continuing campaign it has run against Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party and the role played by the Momentum movement of his supporters. This was somewhat muted after Corbyn led the Labour Party to a wholly unexpected recovery at the last general election but has since been reignited with the accusation of anti-Semitism as the main weapon. Spain’s most influential newspaper, El País, strongly supported Pedro Sánchez’ opponents and did what it could to prevent him from regaining the leadership of the PSOE, arguing strongly against any kind of accommodation with forces to the left of the PSOE. It will now have to eat humble pie as Sánchez has led the PSOE to a remarkable recovery as a result of having shifted its position significantly to the left.

That the political map of Spain has changed as a result of the effects of the economic crisis of 2008 which particularly affected the Southern European countries, including Spain, can be seen from examining the two graphs below. Fig. 2 demonstrates clearly the significant drop in the standard of living which the bulk of the Spanish population experienced. Only Portugal experienced a worse outcome.

Source: World Bank

Fig.2 GDP per capita of sample European countries 1972-2016

Fig.3 Spanish general election results 1993-2019 2

Until the 2008 elections, electoral results largely reflected the “business as usual” nature of Spanish politics with the two main centre-right (PP) and centre-left (PS) parties taking turns in power. This can be seen in Fig.3 above. The PSOE had absorbed much of the ideology of the Blairite Third Way. From 2011, in the aftermath of the economic crisis, both these parties experienced major drops in support. The PSOE was the first to be affected. This was accompanied by the rise of the radical left, “populist”, Podemos which gained support mainly at the expense of the PSOE, particularly amongst younger voters. Podemos built its support on the basis of the indignados movement which had rocked Spain in 2011. At first, unlike other European countries, the loss in support for the centre-right PP wasn’t accompanied by the rise of a far-right party. Ciudadanos, a party which started life as a Catalan party expressing Spanish nationalism in opposition to Catalan independence, was the main winner of the crisis which overtook the PP as a result of corruption scandals. Like the 5Star movement in Italy and Macron’s En Marche in France, it initially rejected any definition of its position on the right-left political spectrum but eventually focused its attention on winning PP voters disaffected because of the corruption scandal and accepted being seen as a party of the centre-right. It is seeking an alliance with Macron’s En Marche for the European stage.

These events show that the major political changes that have occurred have been largely the result of capitalist economic crisis and stagnation. The “party of order” blames the events on the actions of political actors, particularly those of the hated “populists”. By opposing the “populists” of both left and right, it hopes to “bring the country together” so that politics can return to “business as usual”. The Guardian this week has continued its denounciation of populism 3 as a phenomenon, e.g. Populists more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

However, the “populists” are largely benefiting from the changes in popular mood brought about by a generalised lack of confidence in a system in crisis rather than being the cause of the phenomena. The crisis that izs the real cause is both political and economic.

The economic crisis can be characterized by the lasting economic effects of the 2008 great recession which was born disproportionately by different sections of the population. Those who bore the brunt of the ensuing austerity imposed by the government under international pressure were the young, the rural areas, pensioners and low-paid workers. Spain’s Gini index, the measure of economic inequality, increased significantly.

Source: World Bank

Fig. 3 Evolution of the Gini index in Spain

The rate of youth unemployment, those under 25 in Spain reached 55% in 2011, the year that saw the uprising of the indignados, and is currently still 35%. The rural areas have been victims of the longer-term process also occurring in Western countries which experienced deindustrialisation, namely the concentration of economic activity in service industries in the large cities with a consequent depopulation of the rural areas. The demographic profile of rural populations aged as a result. I have highlighted the effects of these changes that occurred also elsewhere in my previous post Reflections on a series of Guardian articles. In Spain the plight of the rural areas has given rise to a specific social movement of the España Vacia (Empty Spain) which took its name from an eponymous book length essay by the writer Sergio del Molino published in 2016.

The political crisis, which I have also highlighted in the same and a subsequent post, is reflected the loss of popular faith in the workings of representative democracy, with conventional politicians being universally seen as self-serving and corrupt. The justified revolt against these trends has taken two main and contradictory forms according to whether the main source of the economic problem is seen to be external to the country, i.e. foreigners, or internal, i.e. class divisions. I am using class 4 in the broad sense of the how much importance is given to economic divisions in society in the way people view their own problems. Class is thus the source of political divisions in the nation insofar as people include fellow nationals in those responsible for their woes (e.g. the 1% v. the 99%). On the other hand, foreigners being viewed as the main source of the problem is a reflection of the fact that the idea of nation is preponderant in people’s identities. Nationalism is thus a uniting factor between classes against a common enemy which lies outside the nation. They could be migrants and/or foreign capital5. Seeing globalisation as the enemy embodies both aspects. I have analysed the polarisation between nation and class in the gillets jaunes movement in France in my previous post Reflections on the Gilets Jaunes protests in France.

In Spain, the rise of Podemos was initially based on the social movement of disaffected young people blaming largely class, perceived in the form of income rather than economic structure, for their serious plight. The 1% v. 99% was the slogan they responded to, as it was in the occupy movement in the UK and US. As Podemos became a credible electoral force, it attracted also the traditional base and voters of the PSOE disaffected with the party’s complicity in the implementation of austerity under the guise of defending the national interest. Pedro Sánchez’ internal struggle to move the party to the left was the result of the realisation that there was a real prospect that unless this move took place, the PSOE would be overtaken by Podemos. The current election results demonstrate that he has succeeded to a considerable extent. To maintain this momentum, he will have to seek an accommodation with Podemos in order to govern. A grand alliance, as in Germany, is impossible for it would risk Podemos benefitting from any failure of a future government in responding to popular aspirations at the expense of the PSOE.

On the right, the collapse of the PP vote is largely a result of the political aspect of the crisis. The involvement of all layers of the party in the Gurtel corruption scandal, including its leader Mariano Rajoy, fatally damaged its credibility. The main winners were the upstart Ciudadanos. Ciudadanos benefitted most from upsurge in Spanish nationalist feeling in other autonomous regions created by the Catalan crisis. It was, after all, a party which rose from its origins in Catalonia as the Catalan party which most vehemently opposed Catalan independence and defended the unity of Spain. It attracted the vote of the upper professional middle classes who had been largely insulated from the effects of the crisis by presenting itself as a progressive nationalist party. This is also the main constituency of Macron’s En Marche in France. The nationalism of Ciudadanos also appealed to the left-behind in the rural areas of España Vacía. The dislike of the Spanish petty bourgeoisie for the foreigner, focussed on the migrant crisis, is responsible for a significant part of the PP’s electorate changing its allegiance to the ultra-nationalist and Francoist Vox.

Conclusions

The result of the Spanish elections illustrates well the importance of factoring-in economics in political analysis. My main argument is that the populist political phenomenon is the result of a serious crisis of capitalism in both its economic and political dimensions. The political consensus around the concept of defending the “national interest” is only possible when no section of society feels particularly disadvantaged. The precondition for a government being able to maintain this situation under capitalism is healthy economic growth which enables a certain amount of redistribution to take place without any particular section of society feeling seriously adversely affected. In a crisis in which capital feels its vital interests under threat, the consequences of the crisis must be visited on the powerless unable to resist. That is the purpose of austerity, which benefits the interests of capitalists under the guise of defending the national interest. The political polarisation that occurs and which the “party of order” denounces as “populism” is the result of popular reaction to its effects dividing along the two main axes of class (internal enemies) and nation (foreign enemies) as the main culprits. Ultimately it will be in the interests of national capital to support the national side of the argument as this presents the lesser threat. The danger posed by this situation is compounded by the fact that representative democracy has become discredited by the corrupting influence of capitalism on the political actors which the “party of order” wishes to defend.

The “party of order” seeks to return politics to “business as usual” without taking into consideration the economic factors which have led to justifiable popular discontent. In presenting populism of the left and populism of the right as two sides of the same evil, the “party of order” risks being left without a constituency because it doesn’t recognise the justice in people’s disaffection with a system which is failing to fulfil their basic economic needs or their desire for effective representation of their interests through the workings of representative democracy. The restoration of economic growth is therefore fundamental for the renewal in the fortunes of the “party of order”. However, the “party of order”, as represented by the Guardian, is currently sounding the alarm over the seriousness of the environmental crisis apparently unaware that this stands in contradiction with its desire for the restoration of normal business which necessitates healthy capitalist economic growth.

In the current Spanish elections, the increased polarisation that has occurred with the shift in the position of the PSOE to the left and the rise of alternative nationalist parties critical of politics as “business as usual” on the right, seems to have led to an increase in the popular belief in representative democracy. In previous general elections in Spain, electoral participation had shown a tendency to decrease from 80% in 1986 to 66.5% in 2016. In 2019, electoral participation suddenly jumped to 75.7%. Political polarisation, so decried by the “party of order”, seems to have at least somewhat restored popular belief in the workings of representative democracy.

However, the central political dilemma remains. For a left government to be able to fulfil the expectations of its electorate without unduly upsetting the interests of capital, it will require economic growth to be restored. This will depend more on the fate of the world economy than on the specific economic policies of the government. The omens in this respect aren’t good as a new recession in the near future is being generally predicted. The danger is that in the likely event of a left government failing to deliver to the popular expectation of a reduction in inequality and help to the left behind in order to enable them to catch up, the political fallout will greatly strengthen the nationalist right and the forces of neofascism.

[1] The rise of Ciudadanos in Spain has much in common with the rise of Macron’s En Marche in France and with the 5Star movement in Italy, but they have significant differences too. They are all populist in the sense that they present themselves as coming from outside the traditional political elite and attack its corruption. They also present themselves as nationalist parties. However, the 5Star movement is Eurosceptic whilst Macron tries to project an internationalist nationalism. Ciudadanos started out as the Catalan party which opposed Catalan independence and defended Spanish national unity and grew into a significant national party as a result of the secession crisis created by the Catalan parliament and the corruption scandals that engulfed the main conservative party, Partido Popular. It is now challenging the PP for the leadership of the Spanish centre-right.

[2] After 2015, Izquierda Unida, the remnants of the Spanish Communist Party, competed in alliance with Podemos under the title Unidos Podemos in 2016 and Unidas Podemos in 2019.

[3] The Guardian’s long standing disgraceful campaign against the more radical left governments of Latin America that governed from the turn of the millennium, particularly that of Venezuela, as part of its attack on populism deserves a separate analysis.

[4] The economic basis of class in a capitalist economy as conceived by Marx is the fundamental difference of economic interests that exists between (productive) wage earners and owners of capital whose income and wealth relies on profits. This objectively sets up two basic classes: the working class and capitalists. However, for this division to become a dominant factor in politics it would be necessary for workers identify themselves as members of the working class aware that their interests are fundamentally opposed to those of capitalists. As this is not the case in contemporary post-industrial economies, concern about rising inequality can be conceived of as a proxy for class e.g. the 1% versus the 99%.

[5] The prevalence of antisemitism in populist movements of the right and left also reflects this dichotomy. In popular mythology the wandering Jew has no nation and is associated with finance. I intend to examine this question in a future post.

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

7 May 2019

- The rise of Ciudadanos in Spain has much in common with the rise of Macron’s En Marche in France and with the 5Star movement in Italy, but they have significant differences too. They are all populist in the sense that they present themselves as coming from outside the traditional political elite and attack its corruption. They also present themselves as nationalist parties. However, the 5Star movement is Eurosceptic whilst Macron tries to project an internationalist nationalism. Ciudadanos started out as the Catalan party which opposed Catalan independence and defended Spanish national unity and grew into a significant national party as a result of the secession crisis created by the Catalan parliament and the corruption scandals that engulfed the main conservative party, Partido Popular. It is now challenging the PP for the leadership of the Spanish centre-right.

- After 2015, Izquierda Unida, the remnants of the Spanish Communist Party, competed in alliance with Podemos under the title Unidos Podemos in 2016 and Unidas Podemos in 2019.

- The Guardian’s long standing disgraceful campaign against the more radical left governments of Latin America that governed from the turn of the millennium, particularly that of Venezuela, as part of its attack on populism deserves a separate analysis.

- The economic basis of class in a capitalist economy as conceived by Marx is the fundamental difference of economic interests that exists between (productive) wage earners and owners of capital whose income and wealth relies on profits. This objectively sets up two basic classes: the working class and capitalists. However, for this division to become a dominant factor in politics it would be necessary for workers identify themselves as members of the working class aware that their interests are fundamentally opposed to those of capitalists. As this is not the case in contemporary post-industrial economies, concern about rising inequality can be conceived of as a proxy for class e.g. the 1% versus the 99%.

- The prevalence of antisemitism in populist movements of the right and left also reflects this dichotomy. In popular mythology the wandering Jew has no nation and is associated with finance. I intend to examine this question in a future post.