The last issue of the London Review of Books publishes a long article by Jeremy Harding on the gilets jaunes in France entitled Among the Gilets Jaunes. I was very struck by the similarities between Harding’s analysis of the factors behind the movement and my own recent post Reflections on a series of Guardian articles which compares Guardian articles highlighting stories in different parts of the world associated the rise of the far right politicians and parties. Harding says of the gilets jaunes:

…the gilets jaunes first came together beyond the margins of the major cities, in rural areas and small towns with rundown services, low-wage economies and dwindling commerce. They were suspicious of the burgeoning metropolitan areas, which have done well on a diet of public funding, private investment, tourism and succulent property prices. Among them are people who grew up in city centres but can no longer afford to live in them:

and

the gilets jaunes who converge on the big towns on Saturdays are thoroughly 21st-century citizens, left out in the cold by globalisation. The success of their protest depends on social media. They mobilise and reach last-minute decisions mainly on Facebook… About one in four demonstrators in Paris, where I last tried to count (in early February), had their smartphones up, recording as they marched, chanted or struggled through a haze of tear gas. Demonstrations are produced and curated as they unfold, becoming a series of ‘scenes from a demonstration’, with hundreds of director/participants live-streaming or waiting to upload content from their phones at the end of the day.

Harding’s description of the gilets jaunes as a protest movement of those “left behind” very much chimed with my analysis in Reflections on a series of Guardian articles , except that the articles analysed in that post concerned situations which had led to the rise of the far right in various countries and locations. Where might the gilets jaunes movement be placed in the traditional left-right political spectrum? Harding’s LRB article gave some pointers but was far from conclusive. He argued that the movement was decidedly egalitarian, a characteristic normally associated with the left, but which Harding saw as due more to the traditional French allegiance to the concept:

Ultra-egalitarian sentiments are widespread among the gilets jaunes, and hard to gainsay in a country where ‘equality’ is emblematic.

Harding pointed to the prominence of slogans attacking the ultra-rich. This hatred of the rich and of the symbols of extreme wealth was highlighted by the renewed protests this week in the Champs Elysées where the ultra-luxurious restaurant and hotel Fouquet was set on fire. Fouquet was where Sarkozy, the president-king of bling, had celebrated his victory in the 2007 presidential elections (The Paris of the rich is ablaze – and that image will define Macron– The Guardian 21 March 2019)

But what to make of the demands which started the movement: the opposition to petrol price rises and the rejection of the reduction of speed limits in rural roads? These were presented by the French government and the media as an attack on measures that were designed to address the climate change crisis. However, the gilets jaunes replied that actually these measures taken by the government would make the “left behind” carry the burden of dealing with climate change whilst the elites in the metropolites were left untouched.

In order to try to understand better the political meaning of the movement beyond what Harding’s article was able to show, I decided to search for any sociological analyses of it which might have been carried out in France.

The first survey was carried out under the auspices of the Centre Emile Durkheim de Bordeaux and preliminary results were reported in an article in Le Monde on 11 December 2018. An English translation of the Le Monde article was published by Verso. The academic collective “Quantité Critique”, coordinated by Yann Le Lann, a sociologist at the Université of Lille, carried out a survey throughout France of the gilets jaunes the results of which were reported in L’Humanité on the 18 December 2018. At the end of November 2018, after the first month of significant demonstrations, the anthropologist Hervé Le Bras constructed a map of the most significant actions of the gilets jaunes and related it to population density.

From these studies I have been able to build a picture of what the movement represents using elements which all the studies would agree with or, at least, not contradict.

All the studies confirm that in some sense the gilets jaunes is a movement of the ‘left behind”. Hervé Le Bras, however, differentiates this clearly from the poor. He makes the point that if the poor in France are mapped, there is a significant correlation with the areas where the far-right Marie LePen-led Rassemblement Nationale (RN, ex-National Front) has done well. However, there is little correlation between the areas of greatest gilets jaunes activity and the areas where the RN has done well. There is a consensus that the gilets jaunes cannot be considered a far-right movement. More on this later.

Hervé Le Bras argues that there are two main components to the movement. One is rural based, in areas of low population density, but most notably in areas of declining population. These are areas which have seen a significant decline also in public services, including public transport. The population is largely reliant on car transport. The Centre Emile Durkheim survey results showed that 85% of the gilets jaunes owned a car, and the Quantité Critique survey concluded that 83% rely on their car to travel to work. The other main group identified by Le Bras is called peri-urban by him and referred to by Jeremy Harding as the urban margins. It is made up of people living in areas just outside the large cities, many of whom were forced to move there as city housing costs rose beyond their means. Many commute to work in the city.

Data from the Quantité Critique survey suggests that 63% of the gilets jaunes are employees and 17% were unemployed. The median household income of the gilets jaunes was €1,700 per month, about 30% less than the median for all households in France according to the Centre Emile Durkheim survey. However, the very poor were under-represented compared with their prevalence amongst the population as a whole.

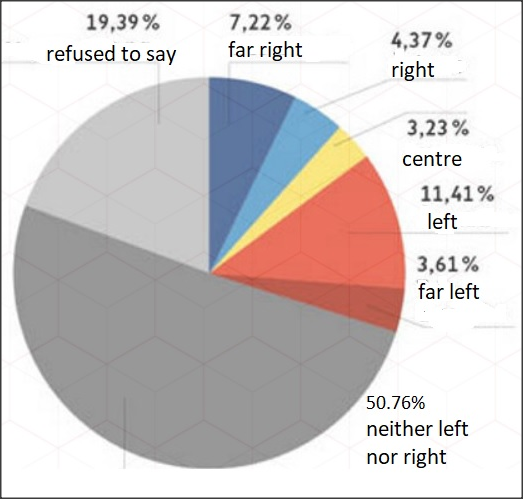

As for their political position, the government and national politicians were universally distrusted, a position held in common with populist movements everywhere. The Quantité Critique survey asked the sample where they placed themselves on the political spectrum. This was the distribution of their responses:

The overwhelming majority refused to place themselves on the spectrum or refused to answer. They were also asked who they had voted for in the last presidential election. The highest votes were for the candidates of the far right and of the far left. 20% voted for Marie LePen (RN) and 20% for Jean-Luc Mélanchon (France Insoumise) compared with 5% who had voted for Macron. 15% had abstained and 9.5% had placed a blank vote. These last two groups together were those who felt alienated from the electoral process made up 24.5%, the largest group of all. But the 40% who voted for what the traditional media and the political centre considers the extremes of the political spectrum also demonstrated the degree of alienation from the political consensus traditionally reigning amongst the elites.

The surveys investigated the gilets jaunes’ attitute to the environment and climate change. 83% agreed that an ecological catastrophe was approaching, but didn’t believe that the solution lay in changing individual behaviour, and structural change was needed. They thought raising petrol prices penalised the less well off most and 62.7% favoured taxing air traffic. Other environmental measures supported included promoting local produce and public transport including reopening closed branch rail lines.

There were surveys also trying to gauge the attitudes of the public as a whole towards the gilets jaunes. When the demonstrations first started 71% of the public were sympathetic to the gilets jaunes according to opinion polls. This declined slowly over time due allegedly to the violence that took place in many of the demonstrations, but as late as the end of January a clear majority of the population (58%) was still sympathetic to the movement. By the end of February polls were announcing that the majority of the French public wanted the protests to stop.

There was also an interesting survey by the polling organisation Ifop for the Fondation Jean Jaurès and Conspiracy Watch on the prevalence of conspiracy theories amongst the gilets jaunes which found that they were significantly more prevalent amongst them than amongst the population at large. There was also an incident of an attack on Jewish philosopher Alain Finkielkraut by a group of gillets jaunes which was prominently reported by the media and led to an outcry and widespread accusations of antisemitism against the gillets jaunes. I intend to leave discussion of these issues to a future post as they have implications that are much wider than the gilets jaunes in France.

Reflections

The most obvious common element that exists between the gilets jaunes and the Guardian stories that I analysed in my previous post Reflections on a series of Gardian articles is that the people involved feel “left behind” and unrepresented within the existing political system. Even more than left behind, they feel that they are moving backwards. The feeling of lack of representation is reflected in hostility to the politicians that operate in that system but also, in common with most other instances of the phenomenon that has been termed populism, in hostility to the traditional media whose political agenda is determined largely by the activities and statements of those same politicians1. This grievance is legitimate insofar as the political system has come to operate in a bubble detached from the needs and interests of ordinary people. This was recognised by Aditya Chakrabortty in the Guardian recently (Britain’s real democratic crisis? The broken link between voters and MPs – March 20) in the case of the UK, but the phenomenon is widespread throughout the world. Chakrabortty also idententifies the reasons for the hostility that exists towards the media:

That vast disconnect between elite authority and lived experience is central to what’s broken in Britain today. Why is a stalemate among 650 MPs a matter for such concern, yet the slow, grinding extinction of mining communities and light-industrial suburbs passed over in silence? Why does May’s wretched career cover the first 16 pages of a Sunday paper while a Torbay woman told by her council that she can “manage being homeless”, and even sleeping rough, is granted a few inches downpage in a few of the worthies? Oh, some may say, they have no connection. Except that the death sentence handed to stretches of the country and the vindictive spending cuts imposed by the former chancellor George Osborne are a large part of why Britain voted for Brexit in the first place.

Divided in space and time

The feeling of being “left behind” has several dimensions which I have referred to in the previous post. One is spatial. The “left behind” reside outside the main cities, in small towns and rural areas. They perceive the main cities as the places where all the action is and from which they feel alienated . This sets up a “centre” v. “periphery” geographic dichotomy. The other dimension is temporal. It is not merely a question of having been left behind but, in the wake of general economic crisis and stagnation, of having actually gone backwards. Communities have aged as young people migrate to the main cities, services have deteriorated and communities feel cut off as rural transport links and post offices close down. The car becomes essential for any form of connectedness to where social action occurs. This creates a society divided in space and time.

Class and Nation

There are two main competing narratives running through the gilets jaunes movement. It seems to me that understanding better the relation between them is essential to an understanding of the current crisis. What follows are no more than some initial thoughts that will hopefully contribute to such understanding. The two competing narratives relate to class politics, on the one hand, and identity politics, on the other. In the case of the gillets jaunes, identity politics refers to nationalism, as other kinds of identity politics seem to have played little role in mobilising the movement.

The two competing narratives are implied in the unusual voting pattern of the gilets jaunes which justifies to a certain extent the description of populism commonly made in the media as coming in two varieties: right and left wing. The 20% who voted for the far-left in the presidential election are those who are likely to have an identity defined more strongly along class lines. On the other hand, the 20% who have voted for the far-right are those whose identity is primarily defined by nationalism. The remaining 60% are likely to have identities defined somewhere in between. The large numbers who consider themselves apolitical, or neither left nor right do not wish to make a choice and try to balance the competing sources of identity. The gilets jaunes as a movement tries to keep this compromise and avoid issues that will bring the divisions to the fore. The elites are the common enemy and they try to maintain the unity in the movement by seeing the elites as “the rich” who have sold out the nation to foreigners by espousing globalisation. This is reflected in the demands of the gilets jaunes which include the defence of French industry by prohibiting its movement abroad, forbidding the sale of French assets such as airports or dams, the creation of a French hydrogen-powered car industry. In this context, immigrants and refugees create somewhat of a problem as they are foreigners but are clearly not part of the elites. The gilets jaunes try to square the circle by demanding that they be well and humanely treated, but they also require them to become French by absorbing French culture and learning French history. They also want failed asylum seekers to be returned to their countries of origin.2

The reference to class shows little awareness of the operation of capitalism as a system and has expressed itself as hostility towards the rich, echoing the feelings in past demonstrations in many countries which pitted the 1% v. 99%. The symbols of wealth and money have been particular targets of violent actions by sections of the gilets jaunes.

Symbols

Laclau and Mouffe in their studies of populism have pointed to the importance of symbols in achieving mobilisation, including human symbols. They have suggested that leaders achieve their power over populist movements because they have somehow come to symbolise the ensemble of aspirations of the movement. Yet, the gilets jaunes have been a horizontal movement which has striven to prevent the emergence of leaders. If there is a human symbol, it is a negative one. The symbol of all their grievances has been the French President, Emmanuel Macron. 3 Trawling through the images of gilets jaunes demonstrations available online, one of the most noticeable features is the relatively absence of placards, slogans and symbols. It seems that the yellow vests worn by everyone somehow symbolise all the grievances. The sparse placards rarely address specific demands and the most common slogans are against Macron and/or against the government in general. “Macron démission” and “Macron, Président des Riches”, or variations of these, appear to be the most ubiquitous. The implication is that the President and the government only represent the rich and not the people. The equating of politicians with wealth is further underlined by the requirement found amongst the set of 42 demands presented by the gillets jaunes that elected representatives earn only the median wage. The alienation from the workings of representative democracy is further underlined by the popularity of the demand for direct democracy through the creation of a system of Referendum of Citizen Initiative, a mechanism whereby groups of citizens can initiate legislation that can be taken to a referendum if sufficient support is obtained.4

Conclusions

Populism is a an expression of genuine popular grievances brought about the operation of a capitalism system in crisis. The similarities between current populist movements in many different parts of the world points to a common cause: the crisis and stagnation of global capitalism and the huge increase in inequality it has brought about. I would suggest a definition of a populist movement as one in which widespread popular mobilisation takes place based on economic and other grievances which are blamed on a distant elite or establishment in which economic and political power is seen as concentrated. This reflects itself in a crisis of representative democracy insofar as vast numbers of people, possibly the majority, do feel themselves unrepresented by those that have been elected ostensibly to represent them. With considerable justification, most politicians are viewed as a self-serving caste and an integral part of the elites or the establishment. Populist movements develop along a path which is structured primarily by the relative importance of class and nation. The concept of class, however, has been largely viewed in terms of a widening chasm in income distribution, the process most clearly analysed by Thomas Pickett, rather than rooted in a sense of exploitation of labour by capital, despite the fact that populism is largely a revolt of the exploited. There is therefore no direct questioning of capitalism as an economic system. I hope to explore the reasons for this in future posts, as well as to analyse further the relationship between nation and class in structuring politics.

Populist revolt is a reflection of a systemic crisis which is simultaneously an economic, political and economic in nature. This has engendered also a crisis in what popular feeling would regard as the “elites” or the “establishment” themselves. The “elites” and/or “the establishment” could be defined as being composed of those who feel largely comfortable with the status quo, but would like to effect changes at the margins through the normal operation of representative democracy which they equate with democracy itself. Those who have traditionally operated as political actors within this system and to whom the Marxist blog critiqueofcrisistheory has aptly attached the epithet “the party of order” feel themselves to be in crisis as their world view and assumptions crumble in the face of the new reality. The pages of the Guardian provide daily evidence for this crisis.

The gilets jaunes movement as analysed here fits well into the scenario I presented in the previous paragraph, but there is a specific dimension which hasn’t been highlighted. Insofar as it is a revolt of the “left behind” who see the past as having been better than the future it is potentially a reactionary movement. Of the party political actors only the parties of the far-right (RN) and far-left (France Insoumise) have been supportive and have operated within it. The “parties of order” have been uniformly hostile and sought to demonise the movement as a threat to democracy. There is indeed a real threat, but the defeat of the movement as sought by the “parties of order” will not remove it. The absence in the movement of a critique of capitalism as a system and the absence of a clear vision of what a different, fairer system would look like as a mobilising factor means that it is likely that the nostalgic vision of a better past will prevail. This means also nation proving to be more potent than class. In a nation with an imperial past this would be highly dangerous. It is highly likely that the eventual political winners from the inevitable end to the movement will be the Rassemblement Nationale or forces even further to the right.

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

30 March 2019

- I intend to deal with the issue of the traditional media and false news in the social media in a subsequent post

- The actual demands with regard to immigrants and refugees are:

(i)That asylum seekers be well treated. They should be housed and education given to the children. Work with the UN to open reception camps in several countries where they can await the result of their asylum requests.

(ii) That those to whom asylum rights have been denied be sent back to their countries of origin.

(iii) That a real policy of integration be developed. To live in France implies becoming French (language courses, French history courses and civic education courses with a certificate at the end).

- It is ironical that Macron himself came to power riding a populist wave in which he presented himself as separate from the political establishment and neither left nor right.

- The demonstrations are very reminiscent of the huge demonstrations in Brazil which eventually brought down the reformist government of Dilma Rousseff. (see my article The Roots of the Brazilian Crisis, p.10).