On Sunday 24th January last, Portugal held presidential elections. This was an event largely ignored by the British press. The Guardian reported the outcome online here. The elections were largely a non-event. There had been no doubt about who the winner would be. The incumbent, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (MRS), an astute politician from the centre-right PSD (Partido Social Democrático), had retained a high level of popularity and was universally predicted to win. He had the lukewarm support of his own party. Only lukewarm because he had developed a good working relationship with the centre-left government of socialist Prime Minister António Costa. In return, Costa’s own party declined to put up an official candidate against the incumbent. This led to a split within the PS. A candidate from its left-wing, former Member of the European Parliament Ana Gomes, ran unofficially but failed to win the support of the parties further to the left, the PC (Communist Party) and the BE (Left Bloc ). These have been keeping Costa in power as he doesn’t have an absolute majority. The PC and the BE each put up their own separate candidates. The result was a runaway win for Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa with 60.7% of the vote. Ana Gomes came a very distant second with 13%. The candidates further to the left won derisory votes, well below the percentage obtained by their parties in the last parliamentary elections. João Ferreira of the PC gained 4.3% and Marisa Matias for the BE, 3.95%. In the middle of a pandemic, there was an extremely high level of abstention with only 39% of the electorate voting. Presidential elections in Portugal do not allow postal voting. The certain nature of the outcome was another contributary factor to the level of abstention.

The rise of the far-right

The big shock, however, was that André Ventura, presidential candidate for the recently formed far-right party, Chega (Enough!), obtained third place with 11.9%, not far behind Ana Gomes. Portugal, until recently, had seemed to have bucked the general trend in Europe which saw an electoral upsurge of far-right parties in most countries. Chega was only formed in 2019, but had managed to elect André Ventura to parliament in the general elections held in that year. The party took only 1.29% of the vote, but Ventura was elected as an MP because of the proportional representation electoral system in operation in Portugal.

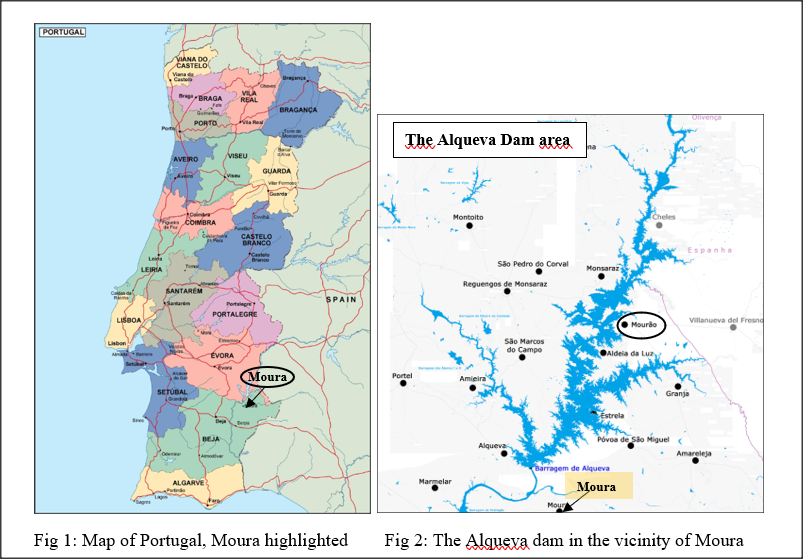

The apparent surge in support for the far-right in such a short time has caused a large amount of consternation and soul searching in the Portuguese left. I was particularly disturbed by noticing that the locality where Ventura obtained his highest vote and came top of the poll was in the lovely town of Moura in Alentejo, an area which had been the bedrock of the Portuguese revolution of 1974. It had witnessed a wave of spontaneous occupations by agricultural workers of the huge landed estates owned by absentee landowners who used them mainly for game shooting and the subsequent formation of agricultural cooperatives, known as UCPs (Collective Units of Production).1

I have been reflecting on the reasons for the rise of the far right in various localities in Europe, starting with my March 2019 blog post Reflections on a series of Guardian articles. In that blog post I wrote that the influence of far-right ideas had gained ground as a

… result of a sea change in the global economy which took place over a very short period and its stagnation since the 2008 Great Recession. De-industrialisation of the industrialised countries has occurred since the 1970s, a period of little more than 40 years whilst industrialisation took centuries to reach its zenith…

The term that has been used to capture all these changes has acquired popular currency is globalisation. But this obscures their fundamental cause, the result of the dynamics of capitalism, of a system whose main driver is the need to accumulate capital rather than responding to real human need. It is the irrationality of this system which produces the ecological and human abomination of a food system which results in the situation that exists in East Anglia, East Midlands and in Almeria and worse in the “Third World”…

It seems to me that speed of change needs to be factored into the analysis. Rapid change has disrupted in a short time the identities of individuals and communities which had taken a long time to form…

A substantial increase in geographic economic inequality occurred over a relatively short time between areas which had a past that mattered because industry was located there when industry was central to the economy and the major metropoles. These became the sole centres of positive economic activity largely organised around consumption…

The sense of areas with a past but no future is compounded by the accompanying demographic changes. As the young migrated to seek a future elsewhere, those who were left behind were the old, the incapable and the unqualified.

I have also been working with Migrants United, a Portuguese community organisation of younger migrants to the UK who emigrated from Portugal as a result of unemployment caused by the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing government austerity measures. There was universal concern with vote obtained by Ventura. We devised a plan to conduct a form of action research that will hopefully come up with some guidelines on the common causes for the trend and how to combat it. We are studying the socio-economic conditions in the parishes where Ventura had the highest vote. We are contacting left organisations and academic researchers in the areas where the parishes are located to help us with the research. When the research is concluded we will organise a Zoom conference involving local activists in all these areas to discuss the results of our research.

Moura

I sought to establish whether the thoughts first expressed in my blog post Reflections on a series of Guardian articles reproduced above applied to the town of Moura in the Alentejo and, in particular, to the parish of Póvoa de S. Miguel. In Moura as a whole, André Ventura won 30.9% of the vote and Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa 41.2%. In Póvoa de S. Miguel, Ventura came top of the poll with 41.2% to Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s 30.8%.

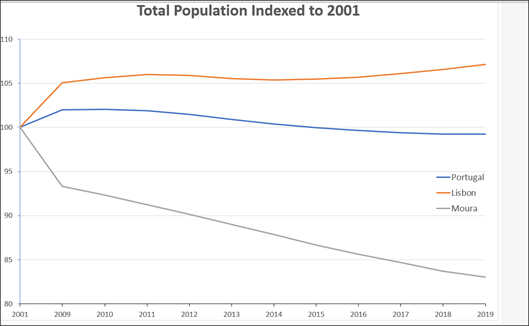

On practically all criteria, Moura fits the description of an area in relative decline. Its population has been declining for a long time.

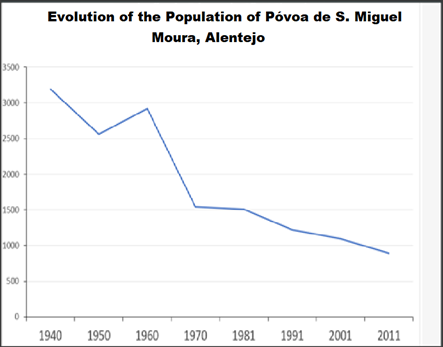

The chart above shows the evolution of the population of Póvoa de S. Miguel, the Moura parish where Ventura topped the presidential poll. The temporary effects of the 1974 Portuguese revolution can be seen in that it managed to arrest for a while the decline in the population. The sharp drop in population in the 1960s and 70s was due to large scale emigration to Europe, primarily France, which also affected most of rural Portugal.

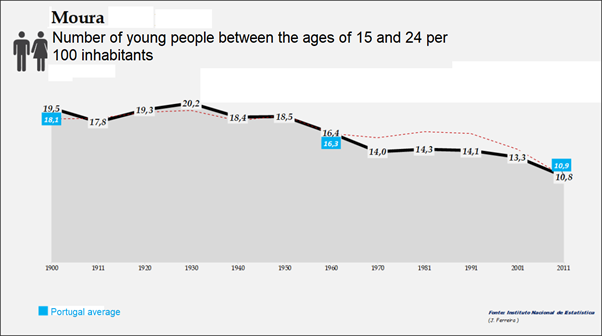

Moura population has also been ageing.

Note the acceleration in the decline in the relative number of young people after 2001.

A 2018 report on the social and health conditions in Moura describes the area in the following terms:

The Moura district follows the regional pattern of a decline in population due to outward migration particularly by the younger population, resulting in an ageing population and degradation of the urban tissue. In the last decade, the district lost 1,423 inhabitants, and it has lost 50% of its population since 1950…

Families show profound economic deprivation, with very low pensions, long term unemployment, low levels of employability linked to a high level of reliance on state benefits…

Moura has one of the highest levels of illiteracy in Portugal, which hasn’t been helped by the outward migration of the younger, often better qualified people. In the 2001 census, illiteracy in Moura was 19.1% and in the last census, held in 2011, it was still 12.7%, rising to 16% amongst women.

The Economic Changes

The Alqueva Dam

The Alentejo region where Moura is situated has experienced major economic changes provoked by the construction of the Alqueva dam, Europe’s largest dam, built as a component of the large scale public works policies of António Guterres, the Socialist Party prime minister in power between 1995 and 2002. Guterres is now the United Nations Secretary General. The justification for the undertaking was the irrigation of the agricultural lands of Alentejo, greatly affected by a series of droughts in the 1990s, and as a major contribution to the development of hydroelectric power. The dam was inaugurated by Guterres in February 2002. There was, however, no plan to establish how it might contribute to the development of local agriculture or benefit the local population beyond the vague expectation that with irrigation of the land, Alentejo’s agriculture could be diversified away from its reliance on cereal production and the concentration of land ownership, traditionally in the hands of absentee latifundia owners, reduced. The project cost, up to 2020, more than 2.5 billion euros of public investment, some of which came from the European Union.

The effect it has had on the local agricultural economy has been dramatic. Since 2010, 70% of the cultivated land has changed hands. Alentejo, which has traditionally been Portugal’s main cereal producing region, became a major producer of olive oil and the intensive cultivation of olive trees effectively a monoculture for the region. From being a net importer of olive oil, Portugal was turned into the fifth largest exporter, but 65% of the olive producing land came into the ownership of 6 major economic groups created with multinational investment. Instead of diversifying agriculture and breaking up land ownership, monoculture effectively ensued, the concentration of ownership increased and was transferred from Portuguese aristocratic families to multinational food conglomerates, partly owned by financial equity funds. The Alentejo became an economic extension of next door Spanish Andalucía where the expansion of intensive olive production had been prevented by the shortage of land. The economic groups involved own olive producing land on both sides of the border. In the process, the price of land increased six-fold in 15 years and land speculation became part of the equation for the investors in olive production.

A major tourist development was also planned for the Alqueva dam. In 2010, Socialist prime minister José Sócrates launched its first phase, the construction of a luxury hotel to be managed by Alila Hotels & Resorts, a Singapore-based company specialising in the operation of luxury resorts in exotic locations. The tourist development had been the brainchild of well-known Portuguese businessman José Roquette. Roquette, once the president of leading football club Sporting Lisbon, owns a major wine producing enterprise in the same Alentejo area, Herdade do Esporão. The development, when completed, was planned to contain seven luxury hotels, four golf courses, two marinas and several other facilities, including riding stables and a bird observation centre.

In 2012, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, Roquette filed for bankruptcy of the holding company as the banks refused to continue to loan to it. The holding company, Sociedade Alentejana de Investimento e Participações, had debts of 53 million euros. The company had received 7.2 million euros of government subsidies, out of a total of 49.6 million euros which had been promised. None of the project’s planned developments were completed.

In November 2014, ex-prime minister José Socrates was arrested, accused of corruption, but not in relation to the Alqueva development. He was held in prison in Évora, in the Alentejo, until September 2015 and has been held under house arrest thereafter. The criminal investigation, known as Operation Marquis, is ongoing.

Labour

The dam was constructed largely with African, Brazilian and East European migrant labour. It submerged Luz, a traditional village in the municipality of the town of Mourão. A new village was built from scratch to house the displaced population of Luz village. Mourão, to the North of the lake, housed a large proportion of the migrant labour used to build both the dam and the new village. Mourão is where far-right presidential candidate Ventura had the second highest vote in the recent presidential elections. Moura too saw an influx of immigrant labour to work on the dam and associated developments, mostly from Eastern Europe, and the local council opened a centre to support the immigrants in 2006.

The new cultivation of the olive groves is highly mechanized, and the olive harvest is largely done by mechanical harvesters which shake the trees. However, there is labour intensive work during the harvest period in picking up olives spilt by the harvesters. Immediately following the harvest, the trees become dishevelled and must be pruned, a labour intensive job. This work is largely done by seasonal migrant workers, many of whom then move on to harvesting other crops elsewhere in the Alentejo.

Conclusion

The parallels between this story and the upsurge in support for ultra nationalist, racist and xenophobic far-right candidates in the areas which I have discussed in my previous blog post Reflections on a series of Guardian articles are inescapable. The depopulation and aging of the hinterlands largely as a result of the outward migration of young people, especially the better qualified ones, towards the major cities or abroad leaves those left behind in those areas with a sense of having been excluded from society and the economy and nostalgic for a past which is imagined as having been better. Any new economic activities set up in these areas rely on foreign migrant labour as local labour is in short supply and bring few, if any, benefits to the existing populations, thus deepening their sense of exclusion. The story of Moura in the Alentejo isn’t dissimilar to that of El Ejido in Spain or of Boston in East Anglia.

The political philosopher Hannah Arendt, in her analysis of fascism in her famous book The Origins of Totalitarianism, argues that its social basis is what she calls “the mob”. Arendt defines the mob as the débris from capitalist crises, the déclassés from all classes created by accelerated change generated by capitalism. In the Alentejo, amongst its older inhabitants, are the remnants of both the old aristocratic latifundia landowners and of those who once worked their lands as waged agricultural workers. The latter, for a short while during the period of the Portuguese revolution, had a vision that a different world in which they could control their destinies and produce to meet human need rather than to generate profit might be possible. Neither social group have any longer an economic role to play and are, in effect, déclassés. It is entirely plausible that many will be found amongst Ventura’s voters.

However, the story of Moura also illustrates a facet of modern capitalism development which was absent from the tales of El Ejido and Boston. This is relates to the effects of Government attempts to stimulate regeneration based on public/private partnerships. In these, the Government sees its role as that of stimulating the investment of private capital, nowadays mostly of foreign origin, hopefully with the purpose of bringing new economic life to areas which had become degraded by the ravages of capital migration and the human migration that followed it. Those left behind rarely experience any of the trumpeted benefits of the regeneration undertaken at huge cost to the public purse.

Such is the fate that will await the objects of Boris Johnson’s “levelling up” projects in the so-called “red wall” areas, should any ever come to fruition.

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

3 February 2021

The roll back from the revolutionary gains by agricultural workers began with the application of the 1977 Basic Law of Agrarian Reform, better known as the “Barreto Law”, named after António Barreto, the Socialist Party minister who began to return the UCPs to their former owners through that law. I had known António Barreto in exile and worked with him in the antifascist struggle at a time when he was a Communist Party militant. The last of the occupied lands, nationalised in 1975, had belonged to the UCP known as “A Terra a Quem a Trabalha” (Land to Those Who Work It) in the vicinity of Moura. The last plot was finally returned to the family of the original owners only in 2019. ↩