Preamble

It was my intention to complete and publish this post before the second round of the French presidential elections had taken place. Unfortunately, this wasn’t possible. However, the results of the second round provide no reason to change in any way its content and conclusions. The analysis I make below relies entirely on the evidence provided by the first round results in which voters were free to express their real political preferences. The second round results are largely determined by many voters’ fears of a win for the far-right, xenophobic and racist Marine Le Pen. They in no way represent the true level of support in the country for Emmanuel Macron. This can much better be determined from the first round figures. We may heave a sigh of relief that, this time round at least, Marine Le Pen has been kept at bay. Unfortunately, as you may gather from what follows, this may well not be the case in the future.

Introduction

The results of the first round of the 2022 French presidential elections held on 11 April confirmed once again that the French political scene has been overrun by the phenomenon known by the Western political establishment as “populism”. The eclipse of the traditional parties of the centre-right and centre-left was total. Anne Hidalgo, candidate for the Socialist Party, the party of such well-known past presidents as François Mitterand (1981-1995) and François Hollande (2012-2017), obtained 1.7% of the vote. Valérie Pécresse, candidate for the Gaullist Les Républicains, the main traditional centre-right party, didn’t do a lot better with only 4.8%. The 3 candidates with the highest percentages polled as follows:

| Candidate | Party | Vote (%) |

| Emmanuel Macron | La République en Marche (LRM) | 27.8 |

| Marine Le Pen | Rassemblement Nationale (RN) | 23.1 |

| Jean Luc Mélanchon | France Insoumise (FI) | 22 |

Le Penn has been universally portrayed as the candidate of the far-right, Mélenchon as that of the far-left. Although Macron is now the standard bearer for the political centre-ground, his eruption into the political scene in the 2017 presidential elections came at the head of a movement of popular revolt against traditional politics when he succeeded in presenting himself as outside the political establishment, despite being eminently a member. Having left the Socialist Party government of François Hollande to form an ostensibly anti-establishment movement called En Marche, Macron ran in the 2017 presidential elections on a platform which was populist in the sense that its main trust was an attack on the political class and a call for a “revolution” to overthrow its conservativism, its resistance to change. Macron referred to the need to sweep away its “conformisme de caste” (caste conformism) which he associated with the political and administrative elite1.2Macron combined this attack on the elites with a “progressive” pro-European nationalist rhetoric in contrast with the backward looking nationalism of Marie Le Pen. This was an attempt to respond to both poles of the popular feelings that the culprits for their woes are either (or both) the elites, an expression of class feeling, or foreigners, an expression of nationalist sentiment (See my article Class and Nation in the Age of Populism).3

Thus, all the relative success of three candidates with the highest votes can be considered as expressions of populism, even though Macron’s populism has lost much of its glitter in the aftermath of a term presiding over a continuing increase of economic inequalities.

In this post, my intention is to use the results of the first round of the French presidential elections to test further the validity of the argument I have been developing that the upsurge of populism and the demise of the traditional politics of Western representative democracy owes more to justifiable popular reactions to changes created by the economic re-structuring of the world capitalist economy, particularly since 1980, than to the action of political parties. The parties have merely tried to gain or retain power in the context of representative democracy by reacting to the changes in demography and popular consciousness created by the restructuring.

The broad results of round 1 of the presidential elections appear to support my general thesis. The new cosmopolitan working class, concentrated in the large cities, is supportive of the egalitarian arguments of the far-left. In Paris, Mélanchon topped the poll in 10 of its 18 constituencies. In one constituency, Mélanchon obtained 51%, the highest proportion for any candidate in Paris4. Macron could only muster 21% in this constituency. This very much mirrors the performance of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in London in the 2017 UK general election5.

Le Pen’s highest vote in Paris was 6.9%, although the ultra-racist Zemmour did manage to obtain 16% in the prosperous Paris constituency in which Macron had his highest vote (47%). Le Pen has done particularly well in what were once the centres of Frances industrial might, now devasted by deindustrialisation. Later in this post I shall be examining case studies of the areas where the far left and far right candidates have done particularly well.

The French Political Landscape

I have been developing a scenario which relies on what is largely common to the various Western countries that used their empires to support the industrialisation of their economies and now have become post-industrial nations. There is also much that is common in their political settings and in the way that representative democracy has traditionally operated in them in the post-World War II period.

However, in the case of France (and of Italy) “traditional” post-World War II politics has been somewhat more complicated than elsewhere in the West because of the electoral and industrial strength of its Communist Party (PCF), lined up with the Soviet Union.6 A large proportion of the industrial working class identified with the PCF. In the first round of the 1973 parliamentary elections, near the height of its power, the party received more than 50% of the vote in many constituencies.7 Constituencies where the party had more than 50% of the vote included several Paris constituencies, and all but one of the constituencies in the department of Seine-Saint-Denis. In Paris, the PCF totalled over 30% of the vote in 26 out of the capital’s 37 constituencies. In one of Marseille’s constituencies, its vote was 59%. The same score was achieved in one constituency in Pas de Calais.

In 1978, on the eve of the beginning of the decline of the PCF, in the department8 of Pas de Calais, one of the main industrial hubs of France, primarily based on the coal mining industry until deindustrialisation set in, the PS had 8 deputies, the PCF 5 and the only other party to elect a deputy was the Parti Radical de Gauche, another left party. I have chosen Nord-Pas de Calais for further analysis because it was the region of mainland France where, in the first round of the 2022 presidential elections, Marine Le Penn had her second highest vote9

By 1997 the PCF had lost all its deputies and the PS had a near monopoly in Pas de Calais. In the department, it elected 11 deputies, with centre-right UDF on 2 and the Parti Radical de Gauche having maintained its single deputy. In the 2012 elections, the PS retained 11 of the 12 constituencies now in existence in the department. In 2017, it lost them all. Le Penn’s RN elected 5 deputies, and Macron’s La République en Marche (LREM) 7. A more graphic example of the political effects of the eruption of populism is hard to find.

As already noted, another department in which the PCF had great electoral strength was that of Seine-Saint-Denis, in what became known as the banlieue rouge (red suburbs) of Paris. I have chosen to use it as a mini-case study because in the 2022 presidential elections, it was the department of mainland France where Mélanchon had his highest vote (49% on average, with 61% in one constituency).

Since then, the working class has become divided and travelled politically in opposite directions. The remants of the industrial working class in the once mighty but now deindustrialised and peripheral areas have become attracted to the nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric of Marine Le Pen and her Rassemblement National. What I have termed the new working class in the large cities, young, cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic, better qualified and employed mainly in service industries have gravitated towards Mélanchon’s highly egalitarian and anti-rich discourse.

In order to make my case, I delve first into the demography and economic history of the areas I am using as case studies.

Nord-Pas de Calais

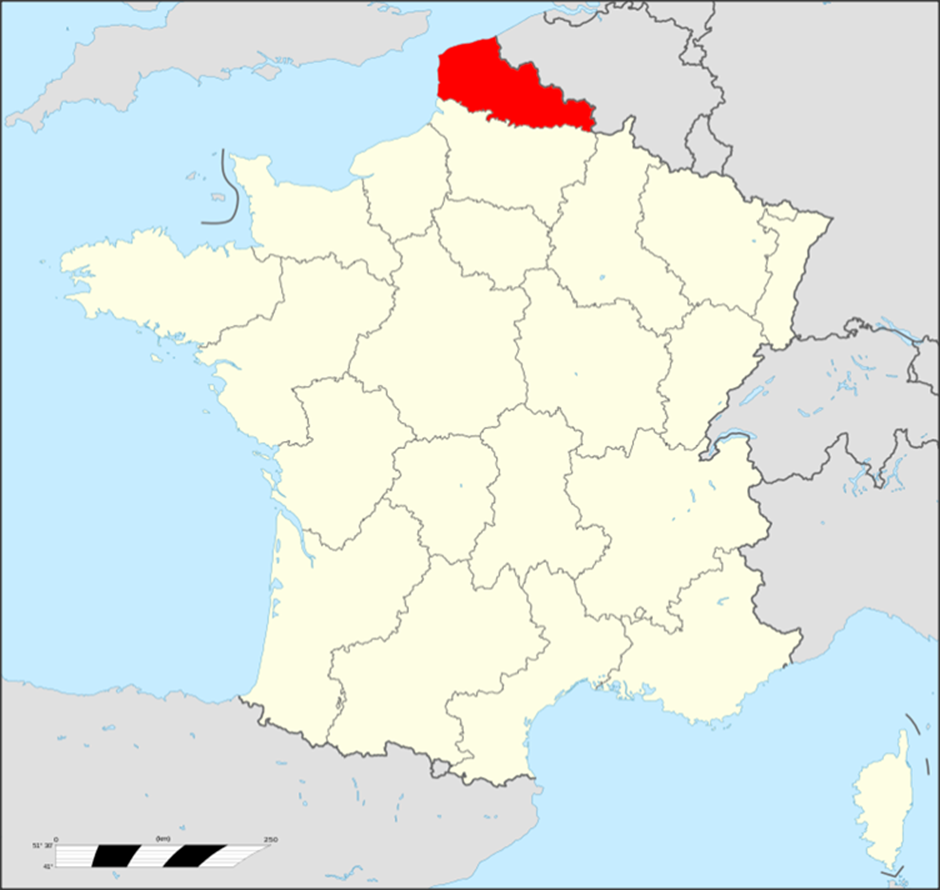

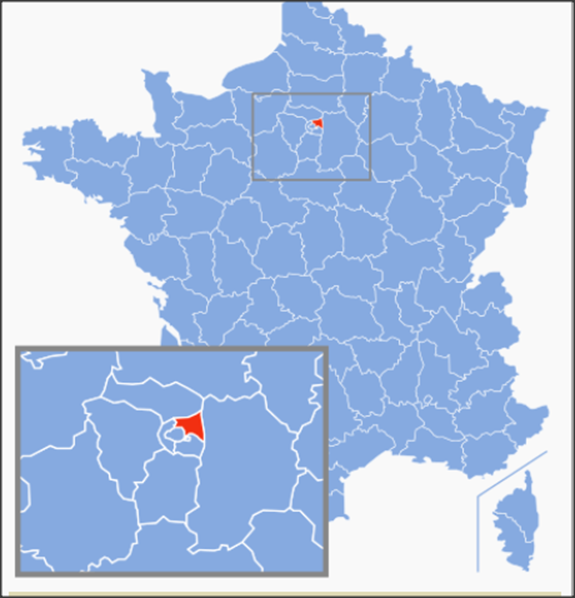

Fig.1 Position of Nord-Pas de Calais region in France

The Nord-Pas de Calais region, comprising two departments, Nord and Pas de Calais, was, together with the Lorraine, the cradle of the industrial revolution in France. The coal mining and steel industries developed around Valenciennes, Douai and Maubeuge (the ‘coal mining basin’), and textile manufacturing was the basis of the seconomic growth of Lille, Roubaix and Tourcoing- see Fig.2 below for their locations. Lille was second only to Manchester in the world wool industry during the Industrial Revolution. Roubaix developed with similiraties to Bradford that remain to this day. The steel industry established itself in the coal mining basin around Valenciennes.

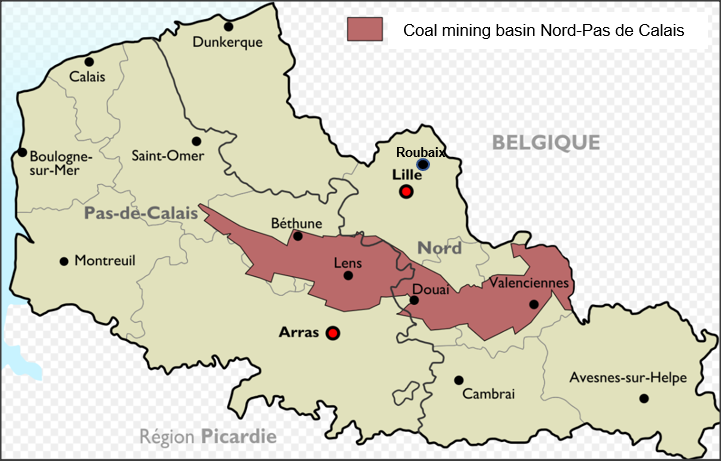

Fig.2 The Nord-Pas de Calais region, showing the position of the coal mining basin

I shall first focus my attention in the coal mining areas of Nord-Pas de Calais, and explore a case study of the constituency where the once a mining town of Bruay-la-Buissiére is located. This is the constituency in France where Le Pen topped the poll on 48%, her second highest vote in the country.

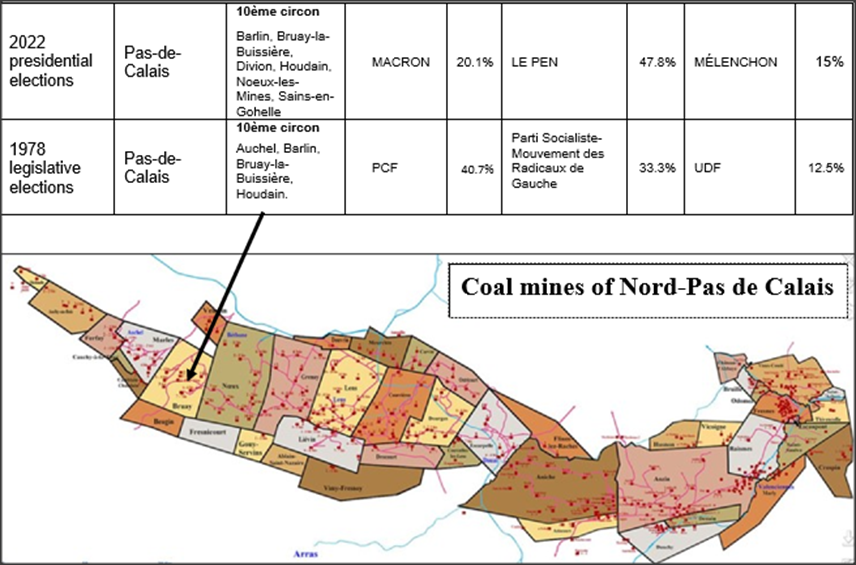

PCF- Parti Comuniste Français; UDF- Union pour la Démocratie Française (centre-right)

Fig.3 Comparative election results in one coal mining area of Pas de Calais

Fig. 3 shows its geographic position and the results in the constituency for the main candidates in the first round of this presidential election, compared with the results in the equivalent constituency in the 1973 legislative elections. In 1973 the left was hegemonic. Between them, the French Communist Party and the Socialist Party won nearly three quarters of the vote. The PCF was the largest party. In 2022, Marine LePen topped the poll by a large margin.

A Brief economic and demographic history of the area

Coal mining in Pas de Calais dates back to the 18th. Century. The first mine in the area highlighted in Fig. 3 was opened in Bruay in 1852. The industry developed and the town’s population grew apace. Between 1850 and 1954 its population of Bruay increased 44-fold from 712 to reach its peak in 1954 of 31,923. In 1934, the Compagnie des Mines de Bruay employed 16,157 people. French mines were nationalised after World War II in 1946. The state company instituted a number of restructuring measures in the mining industry to increase productivity and concentrate production in the most productive mines. The population of the town stagnated from 1954 and began a steep decline in 1968 following the progressive closure of the mines, losing 5,500 inhabitants between 1968 and 1982, the year in which the last Bruay coal seam closed.10. In 1987 Bruay joined up with nearby La Buissière to create Bruay-la-Buissière. The population of Bruay-la-Buissière continued to decline and to age. Between 2008 and 2018 the town lost 1,886 inhabitants, 8% of its population. In the same period, the working age population as a percentage of the total declined by 1%. These are the typical indicators of the left-behind areas victims of deindustrialisation that were everywhere attracted to the far-right in the 21st Century.

Seine-Saint-Denis

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seine-Saint-Denis

Fig.4 Position of Seine-Saint Denis in France

The department Seine-Saint-Denis, a “red suburb” of Paris, is a prime of example of my concept of a new working class area. According to the National Institute of Statistics, immigrants number 410 thousand in a total population of 1.2 million adults, approximately a third. It is a young population. More than one half of them are between 25 and 54 years old. They are mostly of African origin, from the mahgreb and sub-Sahara. The department has 160 islamic mosques, 117 catholic churches, 60 protestant churches and less than 40 synagogues. The number of synagogues has been declining since 2000.

A third of the population lives in overcrowded lodgings. From the mid-1950s until the mid-1970s, bidonvilles, corrugated iron and tin shanty towns without basic services, housed many thousands of immigrants of many origins, including Portuguese and Spaniards.

Here is the full table of round 1 results in the 2022 presidential elections for Seine-Saint-Denis. I have included, for illustrative purposes, the derisory vote for the Socialist Party’s Anne Hidalgo who has been mayor of Paris since 2014.

| Constituency No. | % vote | % vote | % vote | % vote | ||||

| 01 | Macron | 19.9 | Le Pen | 8.0 | Mélanchon | 55 | Hidalgo | 1.2 |

| 02 | Macron | 15.6 | Le Pen | 9.3 | Mélanchon | 61.6 | Hidalgo | 1 |

| 03 | Macron | 28.2 | Le Pen | 13.7 | Mélanchon | 34.9 | Hidalgo | 1.3 |

| 04 | Macron | 15.6 | Le Pen | 12.6 | Mélanchon | 57.9 | Hidalgo | 0.7 |

| 05 | Macron | 18.8 | Le Pen | 14.7 | Mélanchon | 50.5 | Hidalgo | 0.7 |

| 06 | Macron | 17.5 | Le Pen | 7.8 | Mélanchon | 56.8 | Hidalgo | 1.3 |

| 07 | Macron | 18.0 | Le Pen | 7.2 | Mélanchon | 55.0 | Hidalgo | 1.4 |

| 08 | Macron | 25.4 | Le Pen | 15.2 | Mélanchon | 35.1 | Hidalgo | 1.2 |

| 09 | Macron | 20.1 | Le Pen | 9.4 | Mélanchon | 49.3 | Hidalgo | 1.4 |

| 10 | Macron | 19.9 | Le Pen | 13.3 | Mélanchon | 48.1 | Hidalgo | 0.9 |

| 11 | Macron | 18.3 | Le Pen | 13.7 | Mélanchon | 52.8 | Hidalgo | 0.7 |

| 12 | Macron | 22.7 | Le Pen | 17.9 | Mélanchon | 37.3 | Hidalgo | 1.0 |

Historically, the Seine-Saint-Denis has been an industrial area for a long time. Up until the beginning of the 1970s it was the greatest industrial zone of France, the location of heavy industry such as gas works, coal fired power stations, metal and chemical works. Also present were electrical industries, transport equipment manufacturers, tobacco and food processing and printers. It is still the location for several of France’s remaining industrial enterprises, now employing a fraction of former numbers.

Politically, Seine-Saint-Denis has always voted solidly left. As noted, in 1978 the PCF held every one of Seine-Saint-Denis’ 9 constituencies. In 1993, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the PCF still held 6 of the now 13 constituencies in the department. By 2012, the PCF had lost all its deputies, largely replaced by the PS which took 9 of the now 12 constituencies created by electoral boundary changes. In the 2017 elections, displaying another facet of the political earthquake that occurred in those elections, the PS lost all its deputies, the PCF regained 1 and Mélanchon’s France Insoumise (FI) won 4. One deputy was elected with the joint support of the PCF and FI.

Conclusion

The results of round 1 of the 2022 French presidential elections seem to provide considerable support for my hypothesis regarding the nature of the populist upsurge and its relation to the concept of working class. They mirror in many ways the political phenomena occurring in various countries. The contradictions generated by the deindustrialisation of many now more peripheral areas which once were the engines of the country’s economy, as the centres of growth moved to service industries in the large cities exploded in the aftermath of economic crisis, stagnation and austerity. The fact that the new centres of growth were staffed by a cosmopolitan, multi-racial and relatively young population created in a large measure by immigration added further fuel to the fire by reinforcing the left behind sentiments of the declining areas.

The political trajectories in opposite directions of Pais de Calais, on the one hand, and of Seine-Saint-Denis, on the other, as a result of the populist upsurge supports my thesis of the political polarisation of the working class between the remnants of the old and the new working classes. The remnants of the old working class are drawn by the vision that the past was better and had brought relative prosperity and national glory which the far-right creates. They largely blame foreigners, particularly immigrants, for their hardships. The new working class is attracted by a vision of a more egalitarian and fairer future created by the radical left. In this case, the culprits of their hardship are seen mainly as the rich elites, an expression of class feeling.

In both cases, it is the mood music provided by the political protagonists rather than the specificities of their political programmes which largely determines political reactions. In the case of Marine Le Penn and RN, it is the perennial presence at her public appearances of the French tricouleur flag and the references to the need to promote the wellbeing of the French people, as opposed to the foreigners living in their midst, that is the main carrier of the message. Le Pen’s manifesto section on immigration sets out clearly the tone of the mood music:

“More and more people living in France do not want to follow French mores, do not recognise French law and sometimes want to impose their lifestyles on their neighbours, at school, at work, in public services, in public spaces. Immigration cannot continue to remain out of control, otherwise France will have to renounce its sovereignty and the French will be obliged to to accept what they don’t want, to live side by side with populations that wish to remain foreigners in France”11.

On the other hand, one of Mélanchon’s constant refrains has been “les riches nous coûtent trop chère” (The rich cost us too much). Mélanchon’s mood music very much mirrors that of Bernie Sanders in the United States who constantly refers to the rapaciousness of billionaires.

The extent of the populist explosion in France is underlined by the political earthquake that the results of the 2017 legislative elections constituted: the complete annihilation of the traditional parties of the centre-right and centre left. This was confirmed in the current presidential elections.

Macron’s political base is fragile. He failed to reach 50% in the first round anywhere in the country. The fate of Ciudadanos in Spain and of the 5Star movement in Italy demonstrates that a stance that is simultaneously anti-elite and a nationalist, thus trying appeal to the remnants of the old working class and a disgruntled petty bourgeoisie, is difficult to maintain. It is likely to be pulled apart by the tensions generated. Macron’s victory in the second round is mostly due to the fear of a Le Pen victory on the part of Mélanchon’s considerable number of voters. They voted for Macron with extreme reluctance as he is now almost universally viewed as the president of the rich. Many abstained. In the almost certain absence of economic growth for the foreseeable future, political polarisation and turmoil is likely to intensify. And not only in France.

Alvaro de Miranda

25 April 2022

Onwards to the new political frontier: Macron’s electoral populism ↩

This strategy mirrors that of Podemos in Spain, a far-left party that rose to electoral significance in Spain in the aftermath of the indignados movement. Its leaders constantly attacked the political class of all traditional parties as ‘la casta’ (the caste) until such time as electoral success enabled it to enter government in coalition with the Socialist Party, by when the term had been dropped. Electoral success reflects the public alienation from traditional representative democratic politics which hasn’t brought any significant solutions to its mounting economic problems and the rising inequalities which accelerated everywhere after the 2007/8 financial crisis. However, the irresolvable contradiction is that electoral success and entering government inevitably means joining “la casta”. ↩

This is a version of the kind of centrist populism which in Italy gave rise to the 5Star Movement and in Spain to Ciudadanos. Both of these, having enjoyed considerable electoral success for a while, have now fallen apart. It is not unlikely that Macron’s La République En Marche will suffer a similar fate under the weight of its political contradictions. ↩

Mélanchon’s highest vote of 62% in one constituency in Seine-Saint-Denis was closely followed by one of 61% in a constituency in the Caribbean overseas department of Guadeloupe. The Caribbean territories of Guadalupe, Martinique and Guyane all provided several constituencies where Mélanchon obtained over 50%. In these constituencies, Macron obtained some of his lowest votes. I haven’t had the opportunity to search for an explanation for this. ↩

see my article Class and Nation in the Age of Populism ↩

This fact had an important role to play in the creation of NATO, of what eventually became the European Union, and the development of the concept of the West. This still reverberates today in the war in Ukraine. I found an article by Conservative M.P. Sir Leonard David Gammans published in the South China Morning Post on May 5, 1949 but dated February 24, urging the US to sign the original NATO treaty which stated: “A year ago it seemed quite on the cards that France would go communist. The French Communist Party tried to stage a General Strike to prevent the Government from accepting Marshall Aid. There were a series of industrial stoppages in the coal mines and on the railways.” ↩

‘La Seine-Saint-Denis : entre dynamisme économique et difficultés sociales persistantes’. ↩

French administrative areas are divided into régions, départments and communes ↩

The highest vote was in next-door Aisne which share many of Pas de Calais’ characteristics of economic decline. ↩

https://fresques.ina.fr/memoires-de-mines/fiche-media/Mineur00092/evolutions-de-la-ville-de-bruay-en-artois.html; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compagnie_des_mines_de_Bruay ↩