In my recent blog posts I have been arguing that under a conception of democracy which equates the term exclusively with that of parliamentary representative democracy, change is limited to what capitalists will allow. Capital operates through extra parliamentary mechanisms which are largely invisible to the mass of the population because the establishment media, dependent as it is on advertising income provided mainly by large corporations, has no incentive to highlight it.

In my blog post Black Lives Matter and the Contradictions of Representative Democracy Part 2- What is democracy? I said

The “health” of the capitalist economy is commonly measured by the state of the stock market index, a measure of how well the owners of capital are doing. Perhaps the most important reason why Jeremy Corbyn is considered unelectable is that the electorate realise that his election on a radical redistribution platform would most likely swiftly be followed by a stock market crash and capital flight from the country that he would be powerless to do much about unless he reneged on all his campaign promises to benefit the many at the expense of the few. The redistribution policies he advocates might well be popular, particularly given the obscene increase in economic inequality that has relentlessly taken place since 1980, but electors feel he will have little chance of implementing them because the markets won’t let him.

The extra-parliamentary politics of capital are considered by the establishment to be a fact of life, not an afront to democracy. Yet, when people take to the streets to challenge the operation of the system, a huge cry immediately ensues that democracy is being put in danger. At the same time, the system does its best to co-opt the protest and ensure that its expression becomes nothing more than symbolic. This is what has happened to the Black Lives Matter movement.

The recent presidential elections in Peru, which I have been following, represent the latest illustration of my assertion. This is what I will try to demonstrate in this blog post.

Background

Peru is a Latin American country with a highly complex political system. Like Colombia, the country’s economy is greatly influenced by the drug trade. In 2012 Peru overtook Colombia as the world’s largest producer of coca, although more recently Colombia has regained first place. However, consumption of drugs in Peru is relatively low, well below the average for Latin America. The overwhelming majority of drug production in Peru is for illegal export, the United Sates being its main market. Its politics were dominated for a long time by the existence of a violent guerrilla movement led by the organisation Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), claiming allegiance to Maoism. Sendero Luminoso conducted terrorist campaigns which affected the inhabitants of the capital Lima. Its popular base of support was mainly in the coca producing areas of the country. It suffered several heavy military defeats in the 1990s, its influence greatly declined, and it splintered. Its remnants are still active in the core of the coca producing areas.

The Peruvian economy, particular employment, is greatly dependent on the informal sector. The most authoritative assessments estimate some 70% of the active population to be employed in this sector. Apart from coca production and the drug trade, illegal contributions to the informal economy include timber production and smuggling in the Amazon region and illegal mining. The formal economy is dominated by the extraction of primary commodities for export. Its biggest exports are copper and gold. Peru also has substantial deposits of the key mineral essential for the production of electric batteries, lithium. In the first decade of the new millennium, the Peruvian economy grew strongly at an average annual rate of 6%, the highest in Latin America. This was driven by the fast rise in world commodity prices, mainly due to the demand generated by the very high growth rate of China. China became Peru’s main trade partner. In 2018, 27.6% of Peruvian exports went to China, compared with 16.7% to the United Sates, its next most important customer. 23.3% of imports came from China, 21.3% from the US.

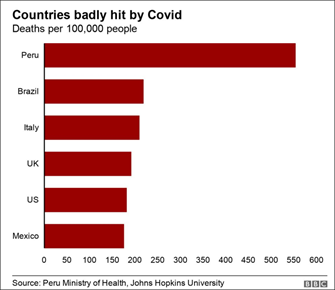

However, the pandemic hit Peru very hard. Peru is the country in the world that has suffered most deaths with the pandemic.

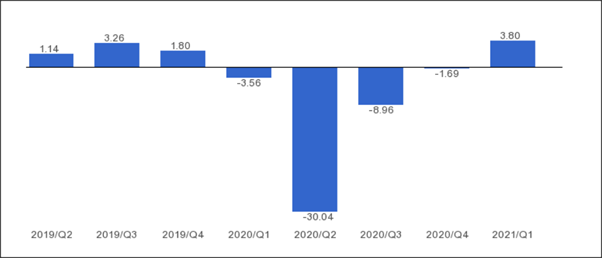

And the economy experienced a huge contraction as a result of the lockdown imposed.

Fig.2 Peru GDP % change, year on year, by quarter

https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Peru/gdp_growth/

Poverty in Peru shot up because of the pandemic. The hardest hit area in the original wave was the capital Lima, including the adjacent port municipality of Callao (see fig.3 below). The income poverty index1 in the capital Lima increased from 14.2% in 2019 to 26.6% in 2020 and in Callao the jump was from 14.3% to 35%! This resulted in large scale migration of the population thrown out of work by the pandemic back to the rural areas they had come from.

Politics

Peruvian politics has been highly fragmented between many different parties largely tied to different interest groups. This is reflected in the make up of parliament. Horse-trading between the parties is the normal business of politics. Deals are made for electoral campaign purposes through coalitions but, even then, no coalition normally gets a majority and further horse-trading is required to form a government. It is very difficult to map the members of Congress on a traditional left-right political spectrum.

Presidential elections occur every 5 years and require 2 rounds if no candidate gets over 50% in the first round. If this happens, the 2 candidates with the highest votes compete in a runoff second round. Voting is compulsory according to Peruvian law.

Peruvian politics are mired in a very high level of corruption. Five presidents elected since 2000 are currently in prison or awaiting trial on corruption charges.

The 2021 general elections

The 2021 general elections were held on the 21April. There were simultaneous elections for the 130 parliamentary (Congress) seats and the first round of the presidential elections. 18 candidates competed in the first round of the presidential elections. None obtained more than 19% of the vote. To the great surprise of the establishment, the highest placed, with 18.9% of the vote, was a previously unknown schoolteacher from the interior rural area of Cajamarca in Northern Peru, whose only claim to fame had been the leadership of the national teachers’ union and of a lengthy teachers’ strike. In second place, with 13.4% was Keiko Fujimori, daughter of a notorious former president, Alberto Fujimori, who has been in jail for several years having been sentenced to 25 years for corruption and complicity in murder. Alberto’s notoriety was for having pursued radical neoliberal deregulation policies in tandem with a vicious war against Sendero Luminoso which included several massacres of Peruvian peasants. His daughter Keiko had promised to pardon him if she were elected.

The runoff second round of the election was held on 6 June between the two candidates, Castillo and Fujimori, neither of whom was much loved by the Peruvian or global establishment. The unwelcome scenario was viewed as another expression of the worldwide populist wave. However, faced with such a choice, the establishment lined up behind Keiko Fujimori. The arguments used for doing so were clearly articulated by Nobel literature prize-winner Mário Vargas Llosa, himself a previous unsuccessful presidential candidate in Peru (Vargas Llosa holds dual Peruvian and Spanish nationality), who declared that the election could not be characterized as being between a humble man from the most deprived sectors of society against the daughter of a dictator, but rather should be viewed as a struggle between democratic freedom (Keiko Fujimori) and totalitarianism (Pedro Castillo). The justification for accusing Castillo of representing totalitarianism was that the main party that supported him, Perú Libre (Free Peru) was led by a man, Vladimir Cerrón, who is a Marxist, a known supporter of the Venezuelan regime and friendly towards Cuba.

The result of the second round was extremely close, with Castillo winning by just 44,000 votes in total of over 17 million. Fujimori, following in the footsteps of Donald Trump, alleged fraud and contested the result. There were calls for the military to intervene if the result wasn’t overturned. Castillo was only confirmed winner on 19 July last, more than six weeks after the election.

Castillo had fought the election on a radical left programme. His main slogan was “No more poor people in a rich country”. The centrepiece of the programme was a promise to call elections for a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. It also prioritised education and health. In his campaign for the first round of the elections, Castillo had said that gold, silver, uranium, copper and lithium mines needed to be nationalised in order to rescue Peru’s strategic resources and redirect the mineral wealth away from rich mining companies to help alleviate widespread poverty. This had sent business circles into a tailspin and upset the stock market. Castillo rowed back in his second round campaign and declared there would be no nationalisations. His revised position was warmly applauded by the Peruvian and foreign business media as a sign of realistic moderation.

However, on July 29, the day after his inauguration, an enormous outcry of disapproval broke out when Castillo named a prominent member of Peru Libre, Guido Bellido, as prime minister. Some of the world media headlines that greeted this event give a flavour of the feelings expressed.

Peru: new president appoints Marxist as prime minister

Appointment of Guido Bellido ends hopes of a moderate government and is likely to spook jittery investors

Peru’s New President, Prime Minister Raise Risks as Debt Tumbles

Investors sent Peruvian bonds sliding in the aftermath of President Pedro Castillo’s inaugural call for a new constitution and choice of prime minister.

Financial Times

Marxist congressman named as Peru’s prime minister

Pedro Castillo alienates moderate allies by picking hardliner Guido Bellido

Guido Bellido, the premier of Pedro Castillo, from admirer of a terrorist to being investigated for excusing it.

The conservative El Comercio is Peru’s main “quality” daily.

Reuters described the reaction of the markets in the following words:

NEW YORK, July 30 (Reuters) – Peru’s currency tumbled to a record low on its largest daily decline in over seven years after new President Pedro Castillo appointed a member of his Marxist party as prime minister and did not yet name a economics and finance minister, leaving the direction of policy and the economy uncertain.

The appointment of Guido Bellido as premier dimmed investor hopes for a moderate administration and sent bond prices lower, with spreads to safe-haven U.S. Treasuries at their widest in over a year.

The 2060 bond issue was down 2 cents on the dollar to trade at 88.3 cents, the 2032 bond fell 1 cent and its century bond was down 2.8 cents, Refinitiv data showed.

The local stock index (.SPBLPSPT) dropped almost 6% at its session low and posted its lowest close since November. On Wall Street, stocks of Peru based financials Credicorp and Intercorp Financial Services fell 16.3% and 10.1% respectively, while miner Buenaventura dropped 5.6%.

The local sol currency lost 3.6% to the greenback to set a record closing low of 4.068 per U.S. dollar.

The decline was the largest for any day in over seven years despite $293 million sold by the central bank to protect the sol.

The markets had made absolutely clear what the minimum conditions were for accepting to live with the new government. This was that Castillo confirmed Pedro Francke, an economist who had worked for the World Bank, generally described by the media as “moderate” (see the Reuters report above) as economics and finance minister. The other condition was that the existing governor of the Bank of Peru remain in post. Bloomberg described the position thus

While investors have been unsettled by some of his proposals, they took solace from the expectation that his chief economic adviser, former World Bank economist Pedro Francke, would take over as finance minister and largely preserve macro-economic policy, albeit with a greater focus on social spending and fighting unemployment.

However, when Castillo named the remainder of his cabinet, the post of finance and justice ministers had been left vacant. The media noted that Francke had left early the inauguration ceremony on the previous day and was declining to comment on why. The speculation was that Francke was refusing to work with the appointed prime minister. Further negotiations ensued and Francke was duly named and accepted the post a day later.

The Guardian announced the fact:

Pedro Francke: relief in Peru as moderate is made finance minister

President Pedro Castillo completes his cabinet after causing shockwaves with appointment of controversial Guido Bellido as prime minister

The markets minimum conditions for peace with the new administration had thus been met and further confirmed when Francke announced that the existing president of the Bank of Peru would be kept in post and that there would be no nationalisations.

However, whether such a moratorium will last is very much in doubt. In an editorial, El Comercio, said of Francke’s appointment:

“… his appointment was received by many as a show of moderation and consensus on the part of the cabinet led by Guido Bellido. This interpretation is a mistake. In the first instance, because of the profile of the person. In comparison with the ultra-radical people that surround Peru Libre, Francke undoubtedly would seem to be an orthodox economist, but the truth is that it will be the first time in many decades that someone with a profile of a not-so-modern leftist- who instinctively sees business investment as something that has to be controlled instead of encouraged- takes the reins of the Ministry of Economics and Finance (MEF).

The most important isn’t Pedro Francke. Whoever wants to see in the new MEF a sign of moderation forgets that this ministry, even though it may be the most relevant, is only a small part of the cabinet. The real worry is the profound mistake in making Guido Bellido president of the council of ministers, and set up with him a team of inexperienced and radical people to lead the country…

…the presence of Francke… has had the perverse effect of legitimating before sections of the population a political option which has never hidden its totalitarian ambitions; ambitions which, in fact, were expressed clearly in the choice of cabinet. In this context, Francke isn’t a moderate conciliator; he is an accomplice…

It is therefore quite likely that the markets and the Peruvian elites will do everything they can and use any means at their disposal, the stock and currency markets in the first instance, very likely impeachment if this isn’t enough, and perhaps even military intervention, if necessary, to ensure that Castillo doesn’t significantly redistribute Peruvian wealth.

Understanding the result

If Castillo’s election can be understood as another expression of the popular discontent with operation of the capitalist system that has affected many countries in the world, including the UK and the US, there are interesting contrasts that deserve to be studied. Whilst in the UK and the US, the left has its best results in the large cities, and the rural areas and smaller towns harbour the supporters of right wing populism, in Peru the reverse is true. Castillo (35.4%) lost decisively to Keiko Fujimori (64,6%) in the capital Lima. Castillo’s strongest support came from the poorest rural areas of Peru.

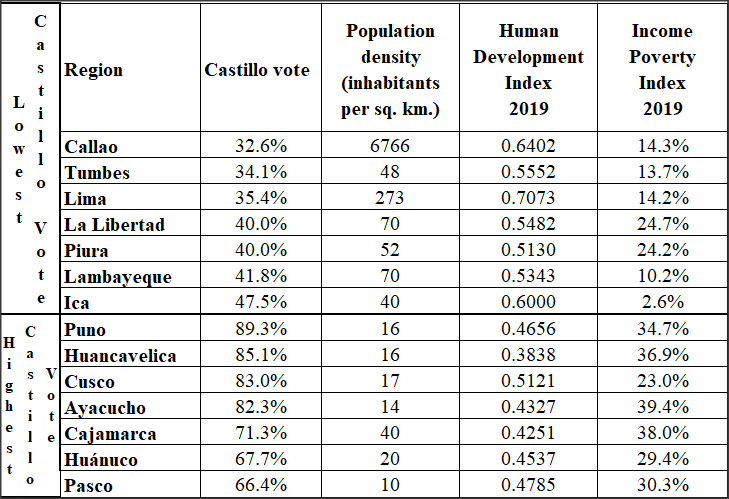

The following table showing the characteristics of the regions with the highest and lowest Castillo votes (see Fig.3 for their geographical location) illustrate the some of the socioeconomic basis of his vote. The population density expresses the degree of urbanisation of the particular region. The gap in poverty rates between the regions where Castillo had his highest and lowest votes is evident in the figures.

Table 1: The socioeconomic basis of Castillo and Fujimori’s vote

As a comparison, the Human Development Index of the UK in 2019 was 0.932.

Lima, the capital, where Fujimori won comfortably with 64.4%, had an income poverty rate in 2019 of 14.2%. Callao, with the highest population density in the country and a similar poverty index is effectively a prolongation of Lima and the Peru’s main port. It is also notorious for the high level of criminal activity.

However, the region of Puno, on Lake Titikaka, on the border with Bolivia, where Castillo obtained his highest vote (89%) had an income poverty index in 2019 of 34.7%, more than twice that of Lima. Puno is a largely rural Andean region with a very large indigenous population. Castillo’s vote reflected to a considerable extent a similar revolt amongst the indigenous population to the one that first propelled Evo Morales to power in Bolivia in 2006 and brought his party back to power in 2020 with the election of his one time economics minister, Luis Acre, to the presidency in 2020.

Castillo has alienated the liberal urban population of Lima because he is a social conservative, something that the media never failed to point out. Castillo opposed abortion, same sex marriages, and stands accused of homophobia. The gender composition of his cabinet is two women and seventeen men. There is little doubt that if Castillo had adopted the identity politics of progressive urban liberals, his rural vote would have greatly suffered. Rural populations in Peru are still deeply religious and subjected to the moral dictates of the Catholic church.

Conclusion

The main purpose of this blogpost hasn’t been to praise Pedro Castillo, however much I may sympathise with his wish to reduce the plight of the poor in Peru. My intention was to demonstrate once again how the system operates to ensure that no-one who is really committed to wealth redistribution is allowed stay in power, should he or she happen to be elected despite the establishment’s best efforts to the contrary. If elected, he or she will be swiftly faced with the option of abandoning the promises made during the campaign or presiding over a collapsing economy. The tell-tale indicators are in the repeated use of the epithets “moderate” to indicate the good guys and “extremist” or “Marxist” the bad ones.

The process I described reveals clearly how the limits of acceptable political discourse, the Overton window of politics, are established and the role that global mainstream media play in doing so. The ideology that underpins the attack on “extremism” and the defence of the “moderates” equates democracy with the defence of private property and, by implication, of the existing wealth and income distribution. Castillo, even though he has been elected by popular vote, is portrayed as being authoritarian, a threat to democracy if he carries out his electoral promises. The reactions of the stock and money markets to his election are depicted as a justifiable defence against the menace of an authoritarian populist threatening to upset the status quo and the existing income and wealth distribution, rather than as an attack on the democratically expressed wishes of the people.

The most likely outcome is that Castillo will end up surrendering to the dictates of the market to stay in power. This is what a previous president elected on a left ticket, Ollanta Humala, did.2

Castillo isn’t in a strong position. His majority was paper thin. He rode a wave of popular discontent, rather than leading a movement for change, and therefore his base is weak and divided. He doesn’t have a majority in congress. In the elections for the 130 parliamentary seats, held on the 11 April, concurrent with the first round of the presidential elections, 10 parties won seats. The highest number of seats went to Peru Libre (Free Peru), the main supporter of presidential campaign of Pedro Carrillo, who ran as an independent, but the party only obtained 37 seats with 13.4% of the vote. It had run in the previous parliamentary elections in 2020 and won no seats. There are moves afoot in Congress to demand changes in the composition of Castillo’s cabinet.

Castillo really doesn’t have much option but to rat on his election promises. If he doesn’t, he faces what happened to Venezuela’s economy when Chávez and Maduro refused to give in to the dictates of the United States. Or, perhaps most likely of all, he will be forced out of power by congress or by the fury of the urban middle classes. This is what happened to Dilma Rousseff in Brazil.

It is difficult to perceive all this as the democratic expression of the will of the people.

Alvaro de Miranda

Alvaro de Miranda is retired from the University of East London where he co-founded a Department of Innovation Studies. He came to the UK in 1958 aged 15 to join his parents who were exiles from the Salazar regime in Portugal. Having experienced fascism, he is particularly alarmed with the recent worldwide electoral rise of the far-right and has been following it comparatively in this blog.

7 August 2021

The income poverty index expresses the percentage of the population who live in households whose per capita spending is insufficient to cover the cost of a basket of essential goods and services. ↩

Humala and his wife stand accused of corruption in Latin America’s most notorious corruption scandal the Odebrecht scandal involving the Brazilian multinational engineering and construction company Odebrecht, now renamed Novonor. A previous Peruvian president, Alan Garcia, committed suicide as he was about to be arrested in connection with this scandal. Another ex-president, Alejandro Toledo, is in exile in the United States awaiting the outcome of extradition proceedings on charges associated with the Odebrecht corruption; another ex-president, Pablo Kuczynski, is under house arrest awaiting the outcome of similar charges. ↩